The Paradox of Light: Necessary but Damaging

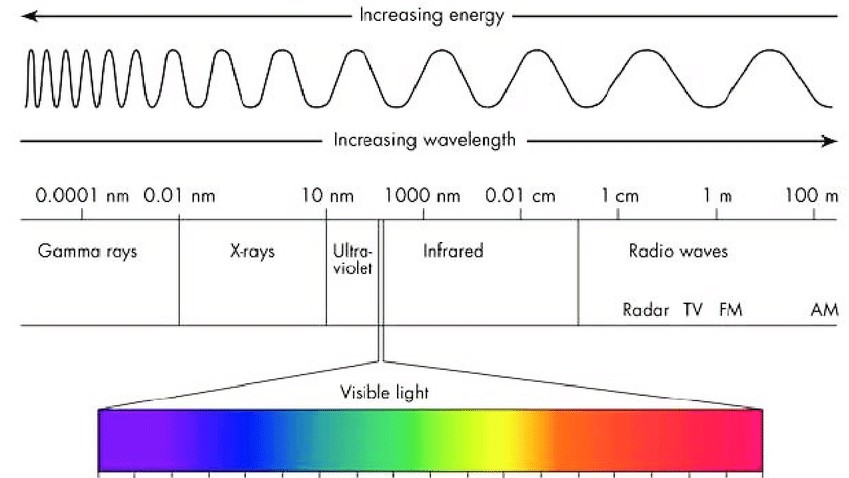

The electromagnetic spectrum, including visible light and the higher energy ultraviolet radiation (Webb 2021).

Among the ten agents of deterioration, one of the most difficult to avoid is light. Everyone knows that ultraviolet light from the sun can be damaging to their skin, but did you know that even visible light can create negative changes in artworks? However, we need light in order to view them, particularly when putting them on display in exhibitions. This paradox results in the need for careful consideration when discussing display conditions for different objects. Many museums have mandatory periods of “rest” for particularly light-sensitive objects, which limit how many months per year the pieces can remain on display, before going back into storage. Why and how are these limits determined? Find out more below, including examples of light damage.

Cumulative and Irreversible

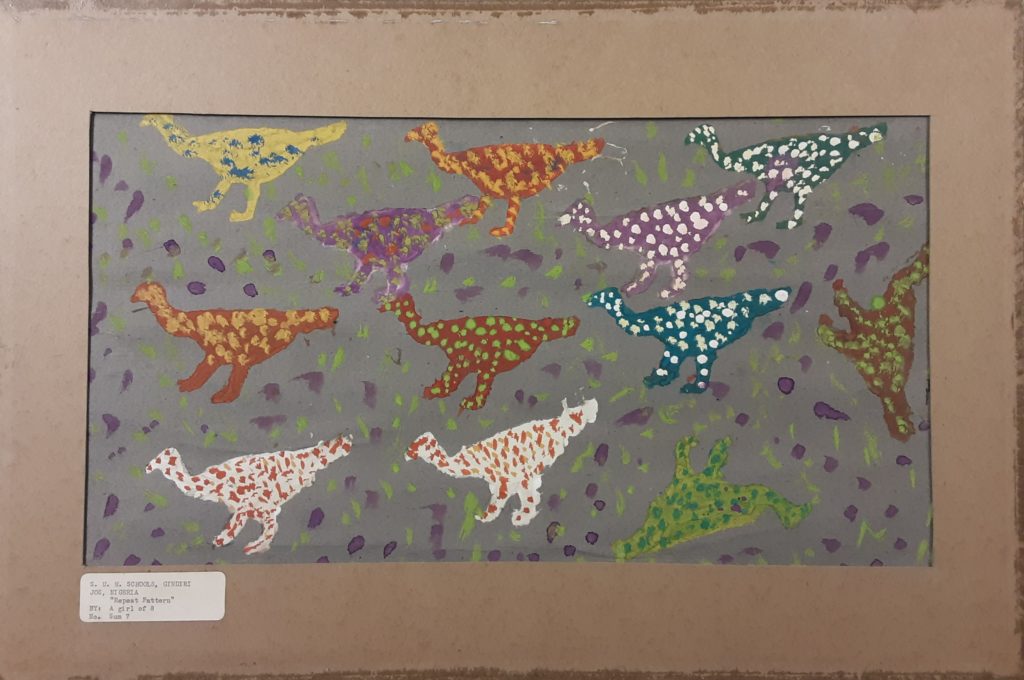

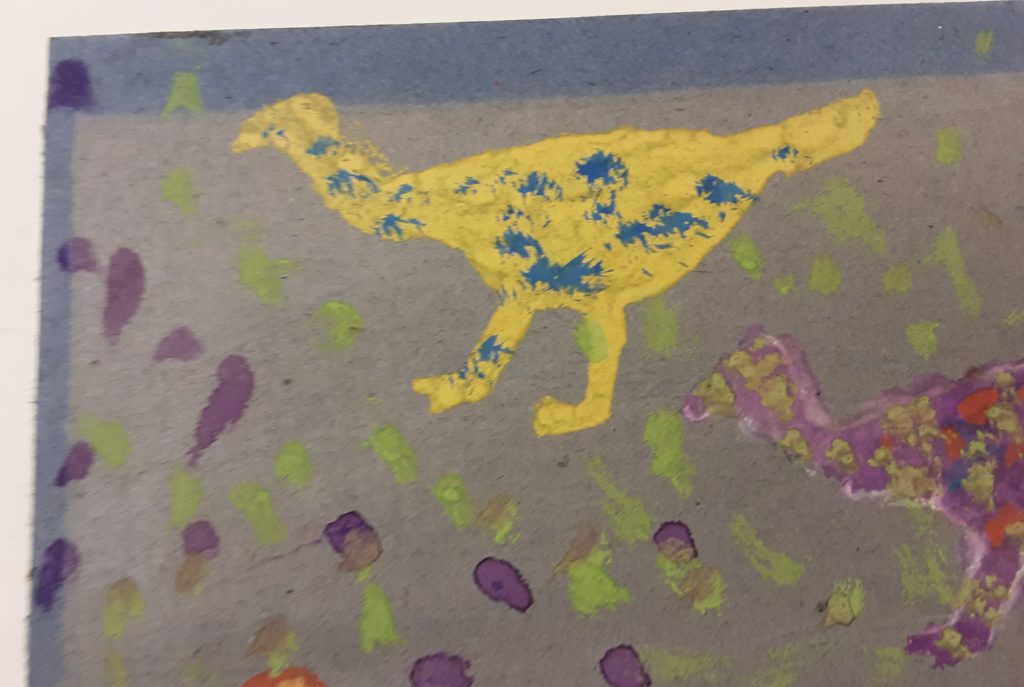

Light exposure and damage is cumulative, meaning that it builds on itself over time, and it cannot be reversed. Many colored dyes are particularly sensitive to fading when exposed to light, and once that happens, it is too late to go back. For example, the student artwork below was executed on paper containing a light-sensitive blue dye, which has now mostly faded to gray. The original color can still be seen around the edges (image on the right), where the paper has been covered by the window mat. Unfortunately, there is no conservation treatment that can reverse these changes and restore the original blue color.

Repeat Pattern by S.U.M. Student, Girl of 8 (Nigerian), Mid-20th century, Tempera on Paper, Gift of the Harmon Foundation, Hampton University Museum, 67.251. Overall (left) and upper proper right corner detail (right).

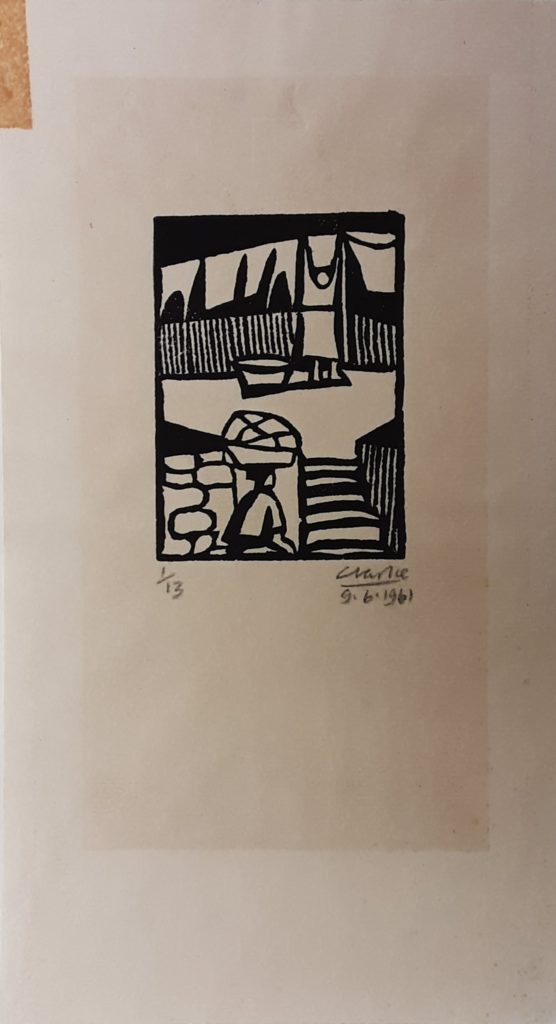

1929-2014), 1961, Woodcut on Paper,

Gift of the Harmon Foundation, Hampton

University Museum, 72.116

Light can also speed up degradation reactions in paper, and cause darkening rather than fading. The piece [at left] has a rectangle of darkened paper in the center, where the piece was likely exposed to light while on display in the past. The outer borders were probably protected by a window mat during this period, and therefore they have not darkened as much. This damage can sometimes be treated through the invasive treatment step of washing the paper (see the previous blog post on Water), which can remove some of the yellowed degradation products. However, this will permanently alter the paper, does not guarantee complete color restoration, and cannot be done to all artworks, depending on the media’s sensitivity to water. Therefore, this damage is considered irreversible.

Testing Options

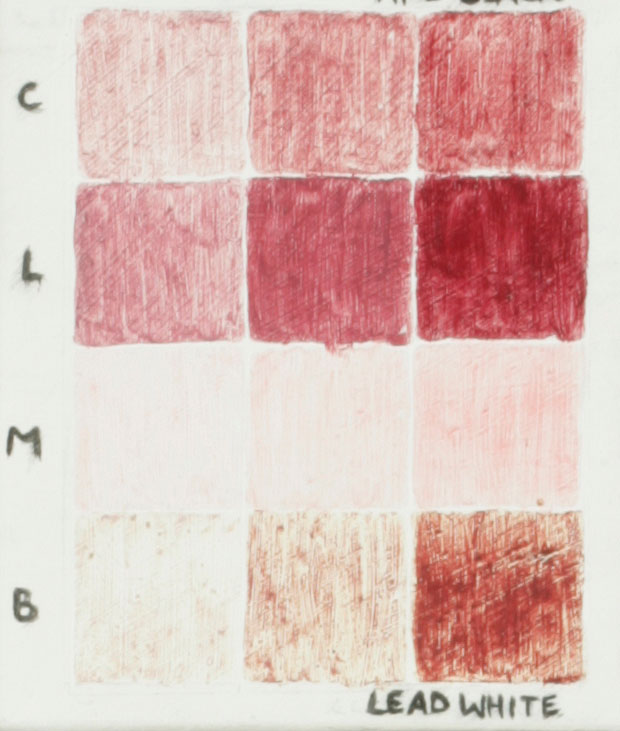

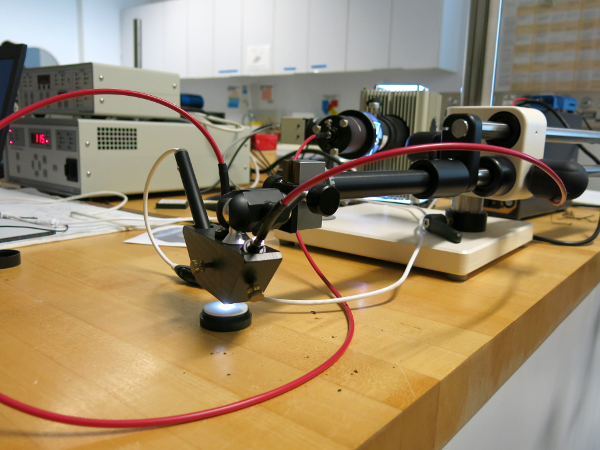

Certain dyes and colorants are known to be particularly light-sensitive (see red samples at left below), so artworks created with such materials are given special consideration by conservators. Testing of the accumulated light exposure in a particular gallery location can easily be done using a Bool Wool standard card [at right]. The eight different fabrics are dyed blue using standardized colorants which each fade twice as quickly as the one next to it in the sequence. By covering half of the card, and leaving it in the gallery for an extended amount of time, the exposed side can then be compared to the covered side to observe how much fading has occurred. Another option is to analyze suspected faders with a micro-fading tester [shown below], which uses a concentrated, microscopic (less than half a millimeter in diameter) beam of light to determine how quickly the actual material will fade over time. The small size of the beam ensures that the test spots are not visible to the naked eye. The results can be graphed and compared to microfading tests of the Blue Wool standards in order to understand how quickly a colorant will fade while on display. There are also machines called colorimeters which can record the exact color measurements of small areas before and after display, but this is a reactive analysis rather than preventive. Conservators prefer to predict and prevent any visible changes to artworks before they happen, since they are irreversible.

Prevention and Treatment (?)

So how do conservators deal with this pervasive and permanent agent of deterioration? Since we cannot reverse its effects, we instead study and predict which materials are in danger of fading, and set limits or conditions for their display. Museums strive to block out any ultraviolet light in their galleries, since it is more energetic and therefore even more damaging than visible light (see the electromagnetic spectrum at the top of the page). In addition, you may notice that paper or textiles in museums are often exhibited under dimmer lighting conditions than the rest of the galleries. These lights may also be motion-activated so that they are only turned on when visitors are around. This keeps the light exposure during display to a minimum, and these objects are usually rotated into storage more often than paintings, ceramics, or metalwork. But these lower lighting conditions and restrictions should be applied to any artwork with light-sensitive components. At home, displaying any art or precious items away from windows and out of the path of direct sunlight is essential to ensure a long lifespan for the objects.

Any light exposure is a trade-off since it can cause permanent damage to artworks, but museums cannot keep their entire collections in dark storage forever. Part of their mission is to provide the public reasonable access to the objects in their care. Striking a balance between these complicated factors is part of what makes this job so interesting and important!

References

Conn, Donia. “The Environment: 2.4 Protection from Light Damage”. NEDCC Preservation Leaflets, Northeast Document Conservation Center, Revised 2012. Accessed 2 September 2022.

Ford, Bruce. “Microfading FAQ”. Microfading.com. Accessed 2 September 2022.

Lee, Christine. “Conservation Tools: The Microfading Tester”. Getty Art & Technology Blog, J Paul Getty Trust, 15 June 2015. Accessed 2 September 2022.

Leonard, Daniela R. “An Exercise in Fugitivity: Investigating the fading of red lake pigments”, E-conservation Journal Vol. 5, 2017. Accessed 2 September 2022.

Michalski, Stephan. “Agent of Deterioration: Light, Ultraviolet and Infrared”. Canadian Conservation Institute, Government of Canada, 17 May 2018. Accessed 2 September 2022.

“The Blue Wool Scale”. Materials Technology, Ltd. Accessed 2 September 2022.

Watkins, Stephanie (compiler). “Standards, Guidelines, and Recommendations for Light Levels During Exhibition”. Photographic Materials Conservation Catalog: Exhibition Guidelines for Photographic Materials, AIC Wiki, July 2004. Accessed 2 September 2022.

Webb, Ashley. “Agents of Deterioration: Light”. Bustle Textiles Blog, 7 Jan 2021. Accessed 2 September 2022.

Whitmore, Paul M., et. al. “Micro-fading Tests to Predict the Results of Exhibition: Progress and Prospects”. In Tradition and Innovation: Advances in Conservation – Contributions to the Melbourne Congress, 10-14 October 2000, edited by Ashok Roy and Perry Smith. London: International Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works, 2000, pp. 200-205.

Explore other articles like this

Art Spotlight: The Abandoned Hut by Mordecai Buluma

In this blog post Angie and Tashae discuss the symbolism behind The Abandoned Hut by Mordecai Buluma as well as the conservation treatment used to prepare it for exhibition.

Tricky Tape and Finicky Frames

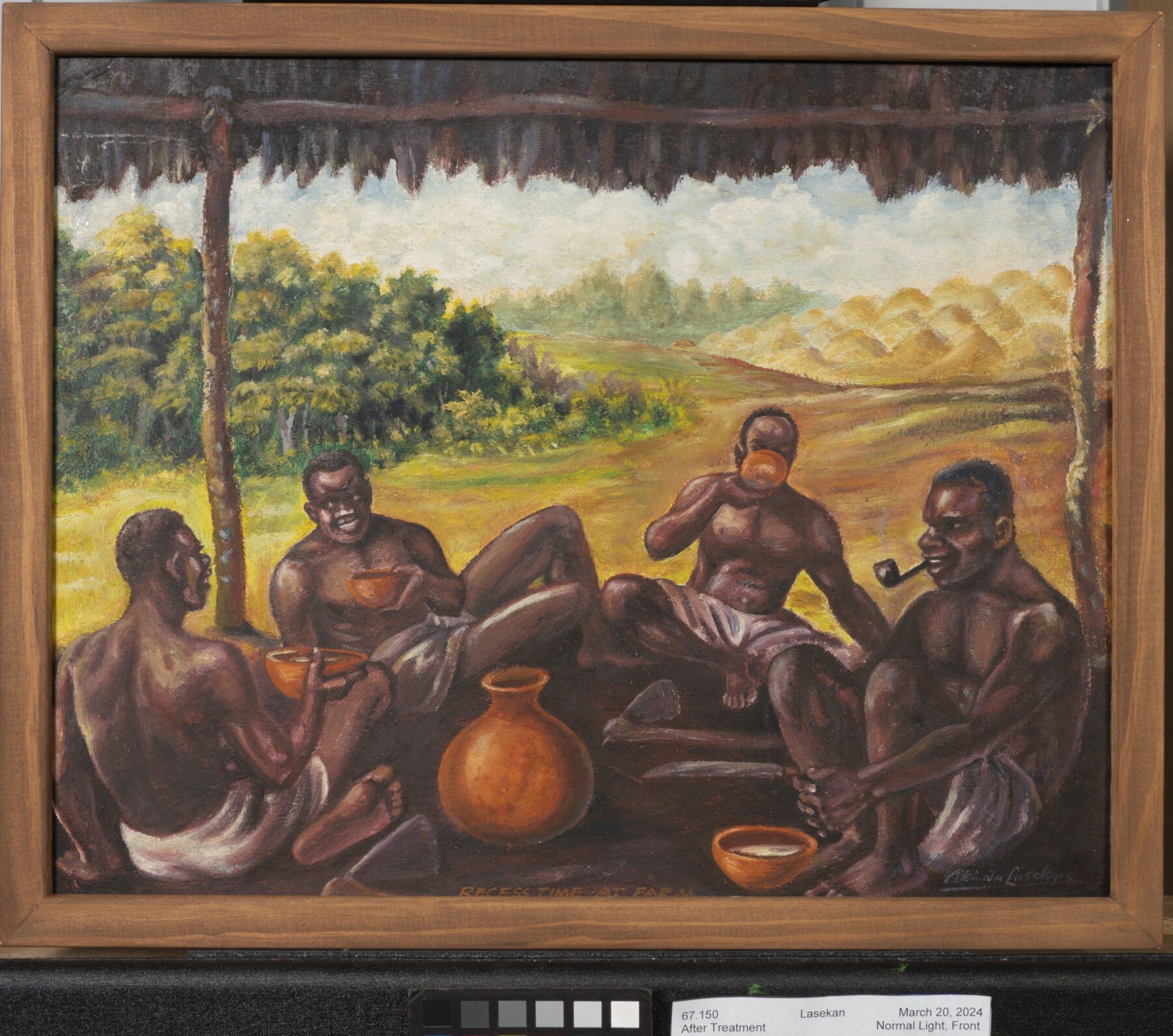

In conservation, tape can be tricky! This post discusses the conservation treatment of the painting Recess Time at Farm by Akinola Lasekan.

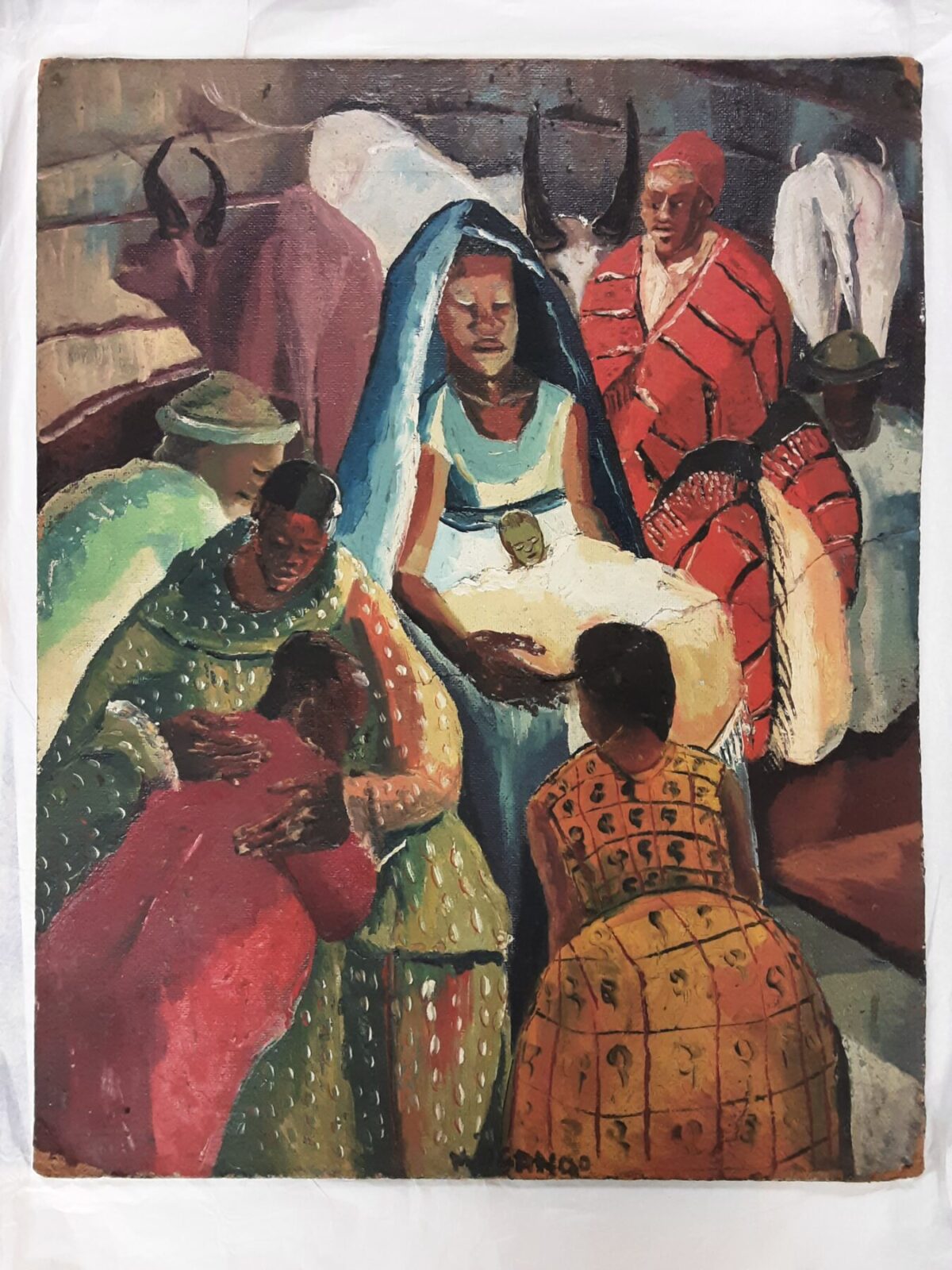

Christ in the Manger: Virginia’s Most Endangered Artifact?

"Christ in the Manger" by Francis Musangogwantamu, along with nine other selected artifacts from other institutions in Virginia, will be featured in an online public voting competition, which will take place from February 20th to March 3rd, 2024. The artifact that receives the most votes will receive the People’s Choice award and a $1,000 grant to be put towards the object’s conservation treatment.