Christianity, Art, and the Harmon Foundation: Part 1

Christianity, art, and the Harmon Foundation. How are these all connected? The Harmon Foundation was, and still is, known for its supporting role in progressing the careers of notable African American artists. Lesser known is its part in opening the American art market to modern African art. However, even more obscured is the Foundation’s role in curating Christian missionary films on Africa. Before its work with Modern African artists, the Harmon Foundation’s first interactions with the continent were through a few missionary films they produced in the 1920s. Later, in the 1930s, Harmon sponsored the Africa Motion Picture Project (AMPP) to create several more Christian missionary films. The films had dual purposes of attracting people back to the Church, garnering support for Christian missionaries in Africa, and serving as proof that Christian missionaries, and by extension colonization, were “civilizing” Africans. For Part I of Christianity, Art, and the Harmon Foundation, we will be learning about the Harmon Foundation’s involvement in creating and producing Christian missionary films.

*Stay tuned for Part II where we will look at Christianity in art within the Harmon Foundation Modern African Art collection at HUM. We will also address questions such as: How are the artists choosing to present their faith? What message is the artwork trying to convey? and Why was some religious art produced by African artists not widely accepted?

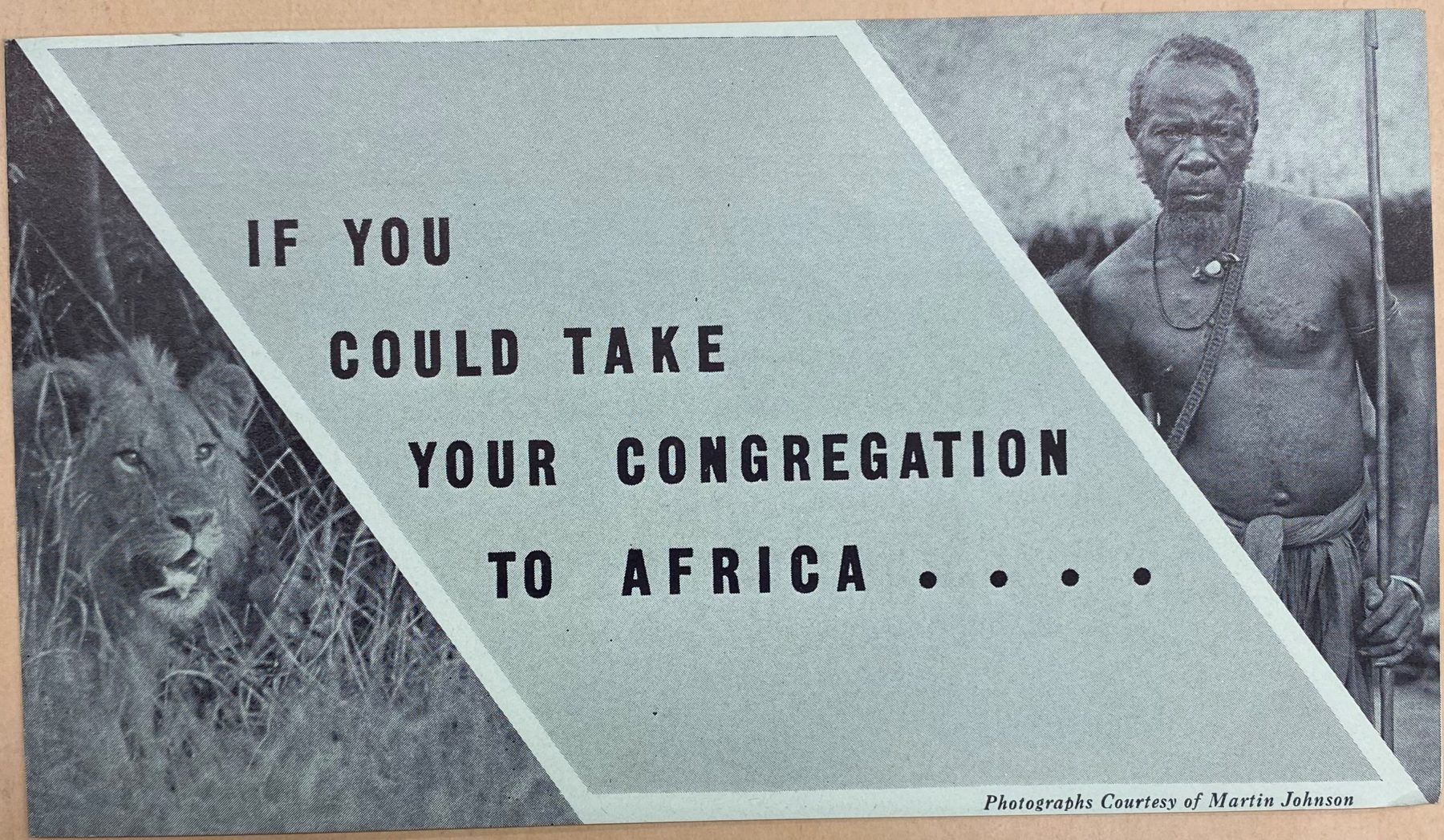

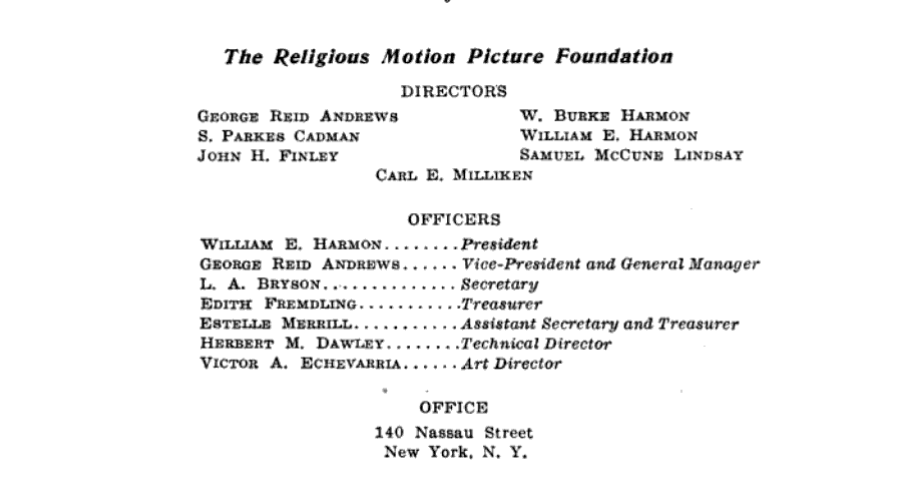

The Religious Motion Picture Foundation

William E. Harmon had received a suggestion that “reverential and beautiful motion pictures as a truly religious character, produced in an artistic way would greatly enrich worship and could become a powerful factor to increase church attendance.” This suggestion was based on the assumption that films could be harnessed as a tool to improve attendance among Protestant denominations. From the suggestion, Harmon created The Religious Motion Picture Foundation in 1925 under the Harmon Foundation’s Division of Social Research and Experimentation. The Division of Social Research and Experimentation concentrated on trial projects to judge if they deserved further development. This Division also included projects “worthy of assistance but which are not likely to become an integral part of its own organization.” By 1926, the Religious Motion Picture Foundation had produced three religious films. Jesus Confounds His Critics, The Unwelcome Guest, and The Unjust Debtor. Within three years, the organization expanded their Christian film endeavors to include three films on Africa. These films: Africa, The Spirit of Christ at Work, The Word of God in Africa; Africa, The Spirit of Christ at Work, Medical Missions in Africa; and Africa, The Spirit of Christ at Work, Christian Education in Africa were created for mission study groups, and touched upon three influential spheres of missionary work: spreading the word of God, establishing medical services, and educational services.

Africa Motion Picture Project (AMPP)

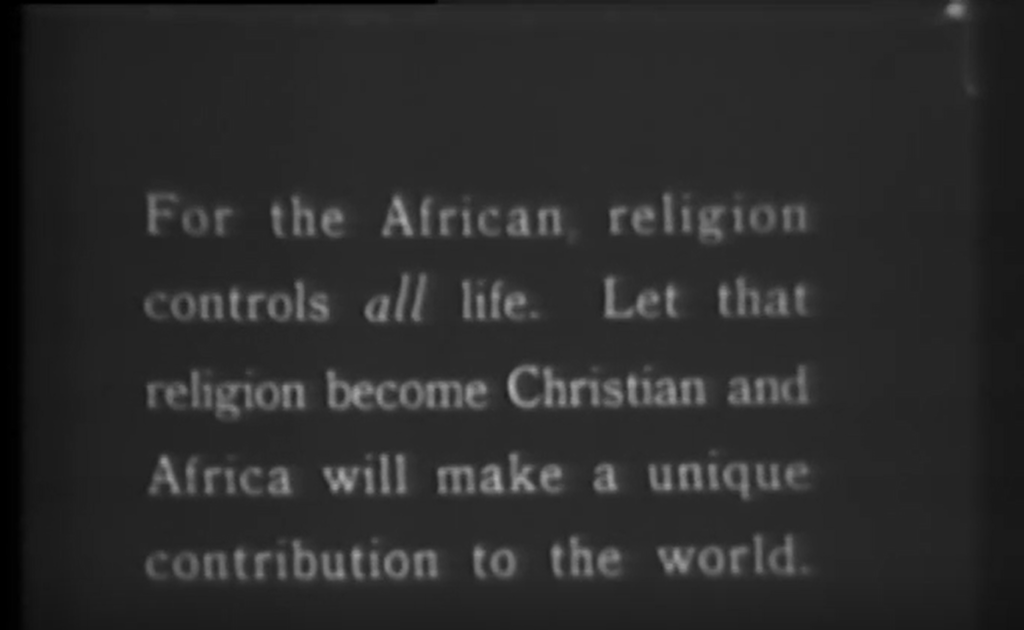

In the 1930s, The Religious Motion Picture Foundation started its partnership with the Africa Motion Picture Project (AMPP), which was created by Disciples of Christ missionary Emory Ross. These three films, Africa Joins the World: Part I, What Africa is; Africa Joins the World: Part II, How Africa Lives; and Africa Joins the World: Part III, From Fetishes to Faith, centered around Christian teaching, church building, and medical care provided by missionaries in the Congo. The films were heavily curated by the Harmon Foundation and other key members of the AMPP. The collaborators “attempted to control virtually all aspects of representation in each film from conception to realization, including storylines, scripts, and image-making in Africa.” The film, Africa Joins the World: Part III, From Fetishes to Faith, opens with the missionaries’ using the word of God and education to move people from superstition of evil spirits to faith in God. The rest of the film takes a turn from the topic of “fetishes to faith” and instead highlights the missionaries’ great contributions to African society, primarily agricultural and trade schools, mission schools, and medical support. Towards the end of the film we learn about the missionary success story of Lutete, a chef, steward, and skilled tailor who ran the Union Mission Hostel. It is important to note that the three films entitled Africa Joins the World were created by using existing footage. These films ultimately lacked the authenticity of the current state of missionary work in Africa. To make up for this, the next nine films created by AMPP and sponsored by the Harmon Foundation were filmed in Africa.

Creating “Authentic” Films

The nine films under the African Film Project included the titles, The Light Shine in Bakubaland – An Epic of the Mission Field, The Story of Bamba, and How an African Tribe is Ruled Under Colonial Government. This last film title does stand out among the other films which largely focuses on missionary work in the Congo and Cameroon. How an African Tribe is Ruled Under Colonial Government uses film to garner support for colonial governments. The film depicts the Belgian colonial government as an integral part of “civilizing” the Congolese. Not only do they provide government jobs, a police force, and appointed village leaders, they also operate as the main judicial body which has been stomping out superstitious tribal laws.

Despite the idea of creating “authentic” missionary films on Africa, the Africa Film Project was scripted by Harmon, AMPP, and to some extent Ray and Virginia Garner, the filmmakers hired to film in the Congo. For example, Ray Garner had villagers construct a temporary graveyard in a better location because of the poor lighting in the original graveyard. Unfortunately, the temporary grave markers created by the villagers apparently did not look “African” enough, so Garner created his own for the film. Although Harmon, AMPP and the Garners had control over the scripts and messaging of the films, they had to rely on the whims, rules, and authority of the local population. The Garners had a difficult time recruiting the local population to star in the films. In order to overcome this problem, they relied on mission-educated Africans who demanded and received pay from the Garners for their time and effort. Furthermore, what the Garners could film and their access to certain areas were restricted, forcing them to negotiate with the local leaders.

The missionary films produced and sponsored by the Harmon Foundation’s Religious Motion Picture Foundation were meant for a Western audience to consume. It was the hope that this consumption would generate additional support for missionary work in Africa, and by extension, support for colonization. This can overtly be seen in the film How an African Tribe is Ruled Under Colonial Government. The producers of the films felt a need to curate films not based on the complete realities of missionary work and the effects of colonization, but based on what they believed their Protestant viewers wanted to see. In that sense, the Religious Motion Picture Foundation moved away from its original mission of increasing the attendance of Protestant churches, to sensationalism in order to sell a Western perception of Christian missionaries, colonization, and Africa.

References

Africa Film Project; How an African Tribe is Ruled Under Colonial Government; Harmon Foundation Collection, 1922-1967; Series: Motion Picture Films on Community and Family Life, Education, Religious Beliefs, and the Art and Culture of Minority and Ethnic Groups, ca. 1930 – ca. 1953; National Archives at College Park, College Park, MD.

Africa Joins the World: Part III, From Fetishes to Faith; Harmon Foundation Collection, 1922-1967; Series: Motion Picture Films on Community and Family Life, Education, Religious Beliefs, and the Art and Culture of Minority and Ethnic Groups, ca. 1930 – ca. 1953; National Archives at College Park, College Park, MD.

Brown, Evelyn S. “Africa’s Contemporary Art and Artists: A Review of Creative Activities in Painting, Sculpture, Ceramics and Crafts of More Than 300 Artists Working in the Modern Industrialized Society of Some of the Countries of Sub-Saharan Africa”. New York: Harmon Foundation, 1966.

Harmon Foundation Year Book, 1924-1926. “Division of Social Research and Experimentation”. New York. Harmon Foundation, 1926.

Journal of Social History, “Africa Joins the World”: The Missionary Imagination and the Africa Motion Picture Project in Central Africa, 1937-9, winter 2010, Vol. 44. No. 2.

Explore other articles like this

The Andrew W. Mellon Fellowship: Now and Beyond

In this post, I will highlight some of the accomplishments of this project and address two main takeaways that can help those looking to reproduce a similar fellowship program.

Art Spotlight: The Abandoned Hut by Mordecai Buluma

In this blog post Angie and Tashae discuss the symbolism behind The Abandoned Hut by Mordecai Buluma as well as the conservation treatment used to prepare it for exhibition.

Opening of I am Copying Nobody the Art and Political Cartoons of Akinola Lasekan

On April 13, 2024, I Am Copying Nobody: The Art and Political Cartoons of Akinola Lasekan opened at the Chrysler Museum of Art. Here are some highlights from the exhibition.