Christianity, Art, and the Harmon Foundation: Part 2

Within the Harmon Foundation Modern African Art collection located at Hampton University Museum, there are a few pieces of art that showcase Christian iconography. Although these pieces make up a small portion of the larger collection, the works are significant when we consider how the subject matter is being depicted. Christianity, Art, and the Harmon Foundation: Part 2, is a continuation of a previous post. In Part 1, we looked at the Harmon Foundation’s use of film to create African Christian missionary films. The purpose of these films were to attract people back to the Church, garner support for Christian missionaries in Africa, and serve as proof that Christian missionaries, and by extension, colonization were “civilizing” Africans. In this post, we will be examining artworks from Brother Francis Musangogwantamu and Elimo Njau, to see how they were interpreting their Christian faith through art.

A Universal Christ

Brother Francis Musangogwantamu was born in 1931 in a small village near Kampala, Uganda. His interest in art began as a hobby around the same time he started his studies for the Brothers of Christian Instruction. Margaret Trowell, founder of the art school at Makerere University, now the Margaret Trowell School of Industrial and Fine Arts located in Kampala, recognized Musangogwantamu’s potential as an artist and asked the higher ups of the Brother of Christian Instruction to send him to Makerere to study. This proved to be successful because he began his art training at Makerere College in 1954.

As a devout Christian, Musangogwantamu tended to create art with “africanized” Christian iconography. This idea of creating religious art that was influenced by African culture, specifically Buganda culture, was not unique to Musangogwantamu. Other artists used their culture, physical surroundings, and contemporary issues to create religious art, as we will see with the artwork of Elimo Njau. While some did accept Musangogwantamu’s art, others held strong objections to his depiction of Christianity. For example, Musangogwantamu had his designs for a mural in a Catholic Cathedral rejected because he depicted Christ as an African man instead of a white man. In response to the notion that Christ could not be African, Musangogwantamu asked, “I wonder…if Christ is not universal?”

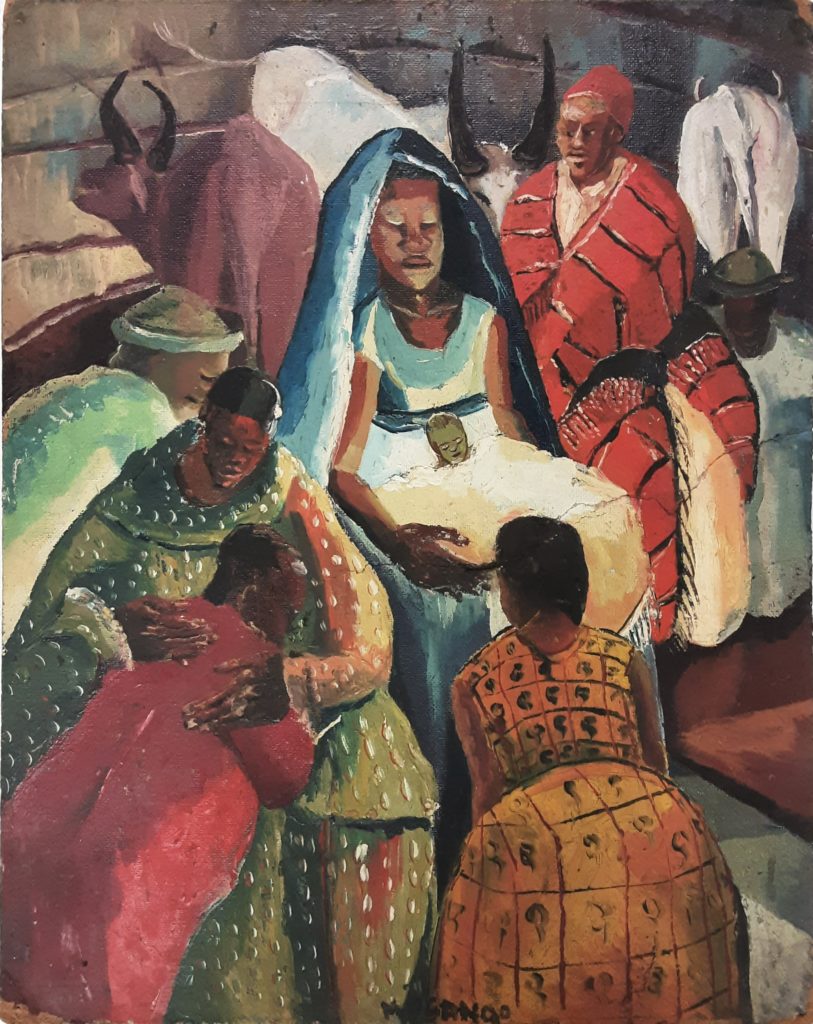

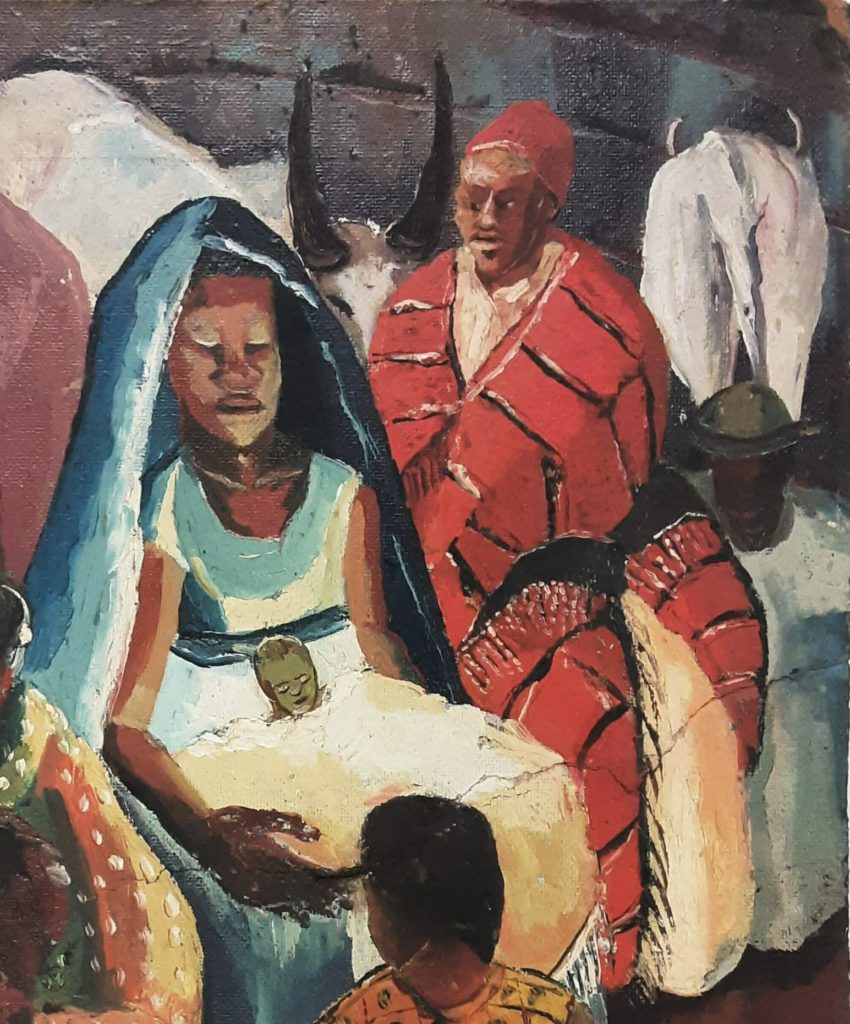

In Christ in the Manger, Musangogwantamu depicts a Universal Christ. Christ, who we can assume is sleeping on the lap of his mother Mary, is the focus of the piece. He positions Christ in the center of the frame with a heavenly light radiating from his body. This light shines on the face of Mary and on the arm of the person to the left of her. Along with Mary and Jesus, there are six other people in the manager and three oxen. Musangogowantamu has painted all the people in the manger black with brightly patterned clothing and with renditions of the Gomesi and Kanzu, traditional women’s and men’s clothing in Uganda.*

According to Musangogowantamu, “If I can succeed to have many poor people buy works of art – no matter even if it is for a shilling, I am sure I will be satisfied just by the fact a message is being passed on through art.” When we think about this quote in relation to Christ in the Manger, we can better understand the importance of Musangogowantamu depiction of biblical figures as Africans. In doing this, he is practicing self-representation. This piece is meant for black Africans to see themselves in a religion that usually excludes them in its art. The message he is spreading is, if we are all made in God’s image, there is no reason Christ cannot be depicted as African.

“I wonder…if Christ is not universal?”

Brother Francis Musangogwantamu

*The Gomesi is a brightly colored floor length dress that includes puffed sleeves, a square neckline and a long sash that sits above the hips. Musangogwantamu’s rendition of the Gomesi can be seen in the bright blue and floor length dress of Mary. Mary’s dress has a squarish neckline but no puffed sleeves. She does have a sash around her body but it seems to be under the bosom instead of above her hips. The Kanzu is a floor length white robe. This seems to be what the man sitting behind Mary is wearing. Under his red and black shawl, we can make out a white, floor length robe. Although the Gomezi and Kanzu are considered traditional outfits especially among Baganda women and men, they do not date back very far. The Gomezi can be traced back to 1905 when Caetano Gomes, a Goan tailor using the design of the suuka, crafted the dress as a school uniform. The Kanzu was introduced to Uganda in the 1840s/50s by Arab traders.

Religious Art with a Dash of Anticolonialism

Elimo Njau was born in 1932 in Tanzania. Like Brother Francis Musangogwantamu, Njau studied art at Makerere College. He is a devout Lutheran known for his mural and public commission that depict the Mau Mau victims and biblical scenes.* According to Njau, he does have a “soft spot for artworks that tell the story of Kenya’s liberation struggle and the Bible in the traditional African manner.”

Njau’s depiction of the Bible in the traditional African manner can be seen in his mural at St. James Anglican Cathedral in Murang’a, Kenya. The mural in the cathedral recounts the life of Christ which includes scenes from the last supper and Jesus’ birth. One particular scene, The Nativity, shows a thatched home in a Kikuyu village that is cut in half to reveal a black Mary, Joseph, and Jesus. The other people in the painting are also black. Although this scene is about Jesus’ birth, Njau places that moment to the top left of the mural. Most of the mural depicts the beautiful Kikuyu landscape which includes a British detention camp. The detention camp is most likely a reference to the camps used during the Mau Mau uprising to detain those associated with the Kenya Land and Freedom Army. Njau’s mural expresses his love of Christianity but also his anticolonial sentiments toward the British colonial system for its treatment of those opposed to colonization. Njau knew the dangers of expressing anticolonial ideas seeing how he did not sign his name on the murals until 2006 for fear that they would have been sabotaged by the colonial government.

“To me art is a direct enrichment to human life and as such art must communicate…As artist we must never escape the call to live more fully and truly in our local surroundings.”

Elimo Njau

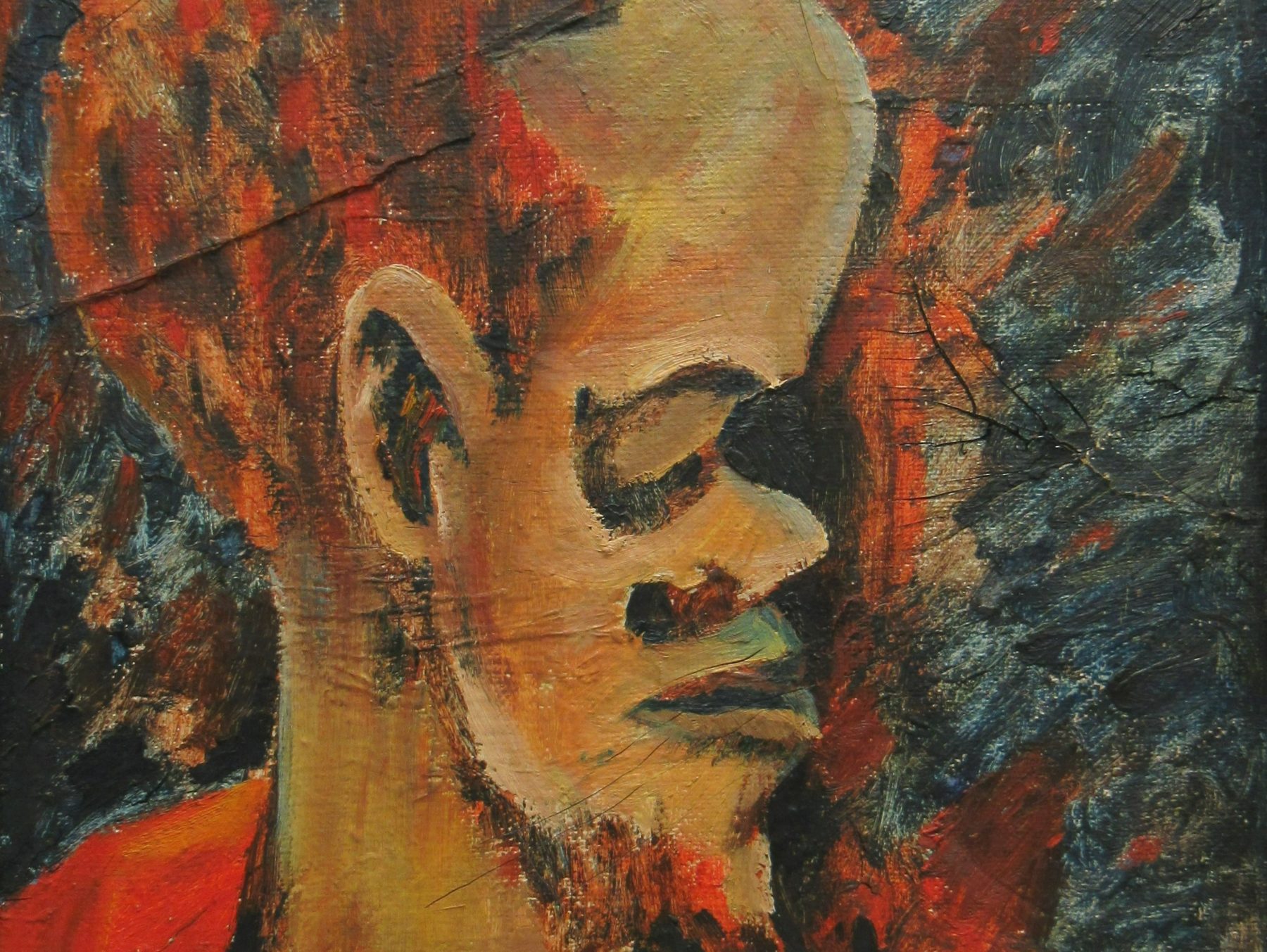

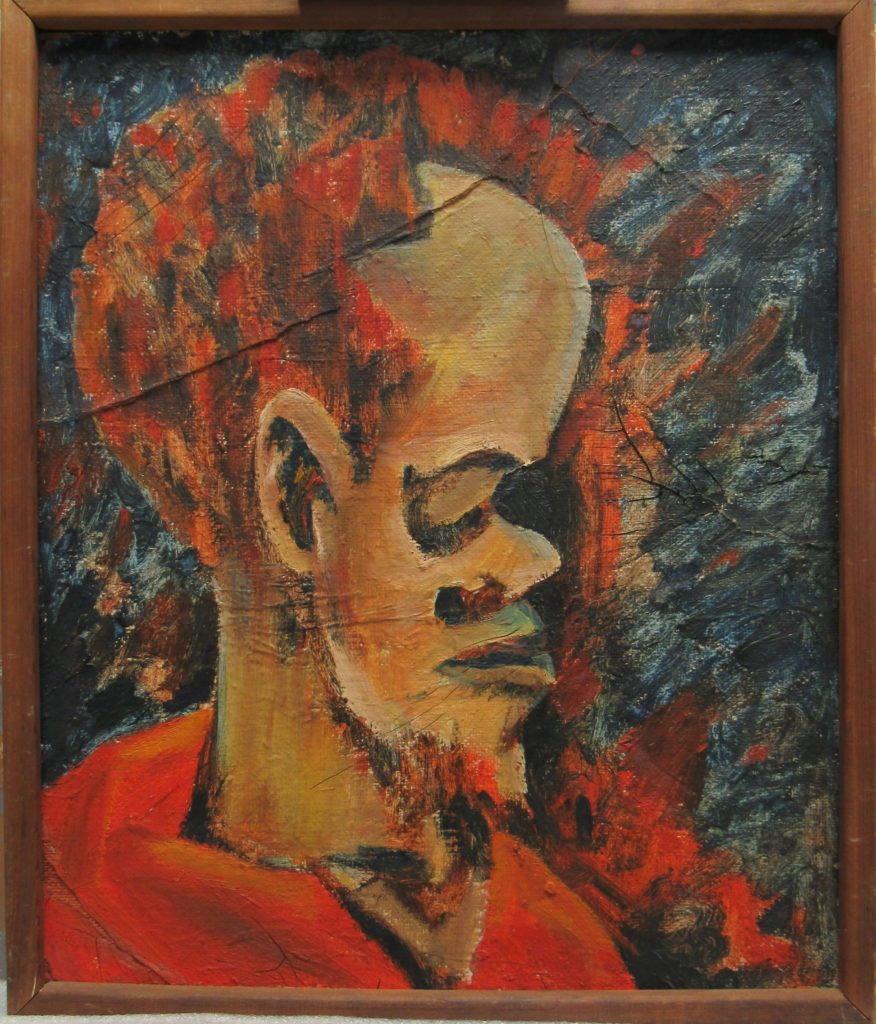

In the painting, Head of Christ, Njau depicts a black Christ in a red top with fire colored hair and goatee. Behind Christ is a swirling darkness. At certain points the color red, which seems to be coming from Christ himself, is layered on top of the dark background. Is the red coloring blood or is it a protective barrier from the consuming darkness? Although Christ is surrounded by the darkness, he stands unaffected with his eyes closed in prayer.

This painting is reminiscent of the scripture Psalm 23 verse 4, “Yea, though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death, I fear no evil, for you are with me.” Whether Njau had a scripture in mind when creating this piece is unknown but a great deal can be said of the depiction of a stoic black man who is within darkness or the shadow of death. Njau did mix Christian iconography with commentary on the oppressive colonial system as seen through the mural, The Nativity. Head of Christ could be painting a similar message of Kenyan resilience in the face of the oppressive darkness of colonization.

*The Mau Mau uprisings was a war between the Kenya Land and Freedom Army and the British colonial government in Kenya. The war to end Kenya’s British colonial system lasted from 1952 to 1960 and ended with the defeat of the Kenya Land and Freedom Army.

Christ in the Manger by Brother Francis Musangogwantamu and Head of Christ by Elimo Njau are two examples of Christian iconography in the Harmon Foundation Modern African Art collection. These examples present the “radical” idea that Christ could be African. In defining Christ’s race as black, these two artists are focused on self-representation more than being radical artists. For Brother Francis Musangogwantamu, the inclusion of black biblical figures in Ugandan outfits presents inclusivity so Ugandan people can see themselves within the Christian faith. Elimo Njau does something similar but he includes anticolonial depictions that speak to inclusivity of the Christian faith and African resilience under colonial rule. Despite these just being two examples of Christian iconography in the collection, they give valuable insight on how some artists were grappling with their faith and beliefs in their art.

References

Brown, Evelyn S. “Africa’s Contemporary Art and Artists: A Review of Creative Activities in Painting, Sculpture, Ceramics and Crafts of More Than 300 Artists Working in the Modern Industrialized Society of Some of the Countries of Sub-Saharan Africa”. New York: Harmon Foundation, 1966.

Elimo Njau: My art, my world, 2006, Nation News.

Kanzu, Wikipedia.

Nativity by Elimo Njau, 2015, Orthodox Christian Faith and Life.

Njau, Elimo,Transition.“Copying Puts God to Sleep” 9. Jun 1963.15-17.

The Gomesi: Uganda’s Treasured Dress, 2019, New Vision.

Reid, Richard J., “A History of Modern Uganda”, Cambridge University Press, 2017.

Explore other articles like this

The Andrew W. Mellon Fellowship: Now and Beyond

In this post, I will highlight some of the accomplishments of this project and address two main takeaways that can help those looking to reproduce a similar fellowship program.

Art Spotlight: The Abandoned Hut by Mordecai Buluma

In this blog post Angie and Tashae discuss the symbolism behind The Abandoned Hut by Mordecai Buluma as well as the conservation treatment used to prepare it for exhibition.

Opening of I am Copying Nobody the Art and Political Cartoons of Akinola Lasekan

On April 13, 2024, I Am Copying Nobody: The Art and Political Cartoons of Akinola Lasekan opened at the Chrysler Museum of Art. Here are some highlights from the exhibition.