What’s in a Name?: Gerard Sekoto’s The Two Women

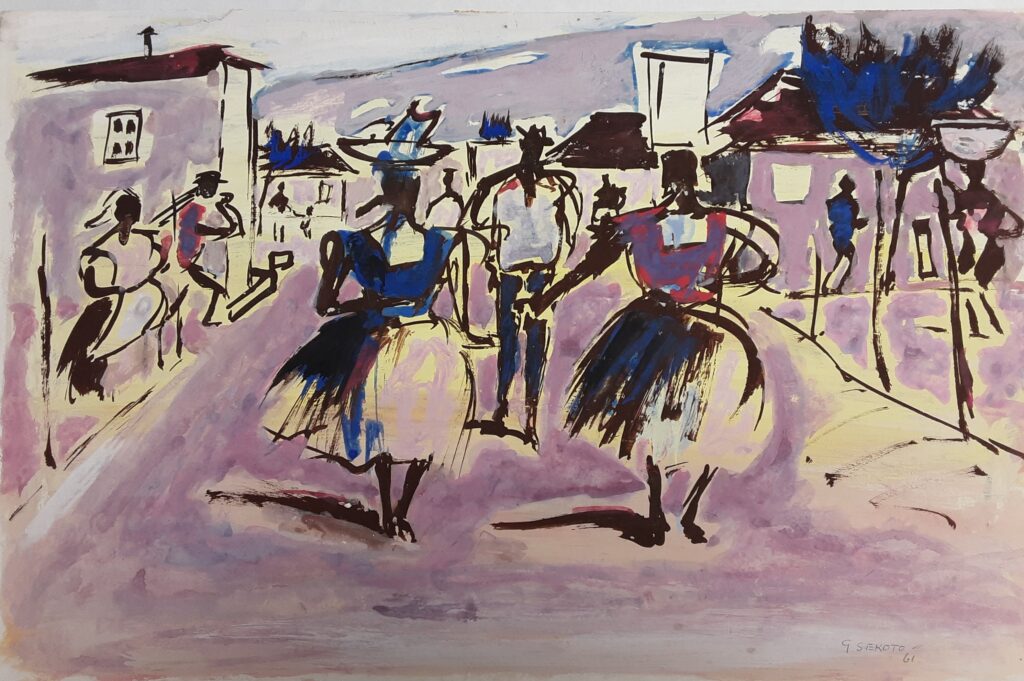

The Two Women by Gerard Sekoto (South Africa, 1913-1993), 1961, Tempera on paper, Gift of the Harmon Foundation, Hampton University Museum, 67.101

What’s in a Name?

“A picture is worth a thousand words” or in our case, a painting. Analyzing a painting can provide information such as the artist’s name (if the painting is signed), the subject of the work, and even the types of materials used. Analyzing a painting can also provide context on a specific time period or culture. Of course, the artwork itself is important but its title can be just as important and revealing. The title of an artwork can be used to better understand the artist’s intent. For this series, we will ask, “what is in a name”, by taking a closer look at titles of artworks to understand how a title can make us question an art piece, change our perspective of a piece and/or reinforce it. Through this series we will come to the conclusion that titles of artworks have considerable meaning and are not always arbitrary.*

For part two of this series, we will analyze Gerard Sekoto’s The Two Women, to present how the title of an artwork, its subject and the artist’s own experience can be used to draw conclusions about an art piece.

*The phrase ”what’s in a name”, comes from the line “What’s in a name? That which we call a rose by any other name would smell as sweet”, from the play Romeo and Juliet. This line, shared by Juliet, is in reference to the idea that Romeo’s last name essentially makes him her enemy, even though she believes he is more than his last name. Shakespeare uses this line to make the argument that names are arbitrary and the essence of an object will not change even if it has a different name.

Who is Gerard Sekoto?

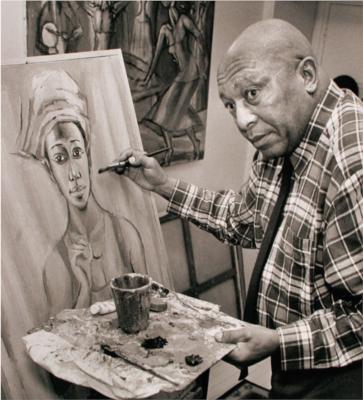

Gerard Sekoto (1913-1993) was born on a Lutheran Mission station in the Middleburg District of the Transvaal, which was once a province in South Africa. At the age of seven, Sekoto started to work with clay and began to draw on a slate board. Eventually, he would learn to use a pencil which he would use to draw his father’s patients. His interest in art continued into his time at college where he would draw his classmates.

Due to the unwillingness to accept black artists into South African art schools, Sekoto was never able to get a formal art education. Despite this he made strides to progress his artistic ability. For example, he learned how to use oil colors from a young white female artist. Because of the serious crime of a black man visiting a white woman, Sekoto would sneak to the woman’s art studio two or three times a week. Eventually, Sekoto took it upon himself to end these art lessons. According to him “should the law ever catch me here trying to be smart, then not a single person on earth could take its teeth away from my throat.”

Gerard Sekoto left Paris in 1947 never to return to South Africa. Sekoto saw Paris as the “Mecca” of the art world and as a place where he could have freedom of thought, something he lacked in South Africa.

Sekoto is considered a pioneer of urban black art and social realism. He was very well aware of South Africa’s social, political and racial differences and in fact chose to actively seek out these differences to paint. Sekoto was attracted to cities such as Johannesburg and Cape Town because they had and still have a diverse population. These cities also had less rigid barriers when it came to social, political, and racial differences.

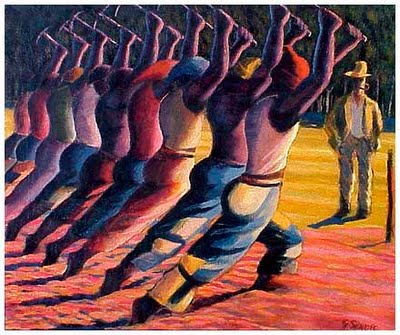

As someone who expressed what he saw and felt through art, Sekoto had a way of viewing both the beauty and ugly in the everyday scenes around him. A great example of this is the painting, The Song of the Pick. In this painting, Sekoto captures the racial inequality of South Africa by painting a white foreman overseeing nine black workers. Although the foreman is in a position of power in terms of employment, his smaller frame puts him at a disadvantage compared to the larger frames of the workers. Sekoto paints all the workers with the same pose, a lunge position with their picks raised above their heads. The strength and repetition of the poses communicates the beauty of unity among black South African workers.

The Two Women

The painting, The Two Women, positions us in a busy street scene filled with hues of red, pink, and blue. The abstract figures around us are hastily drawn with quick strokes of dark brown paint. As we stand in the center of a broad street, we see two women walking with their backs facing us. In our line of vision we also spot a taller man walking in the opposite direction of the women.

The title of the piece immediately draws our attention to the two women in the middle of the street despite the fact that there seems to be other women in this painting. One woman wearing a pink top can be seen to the left and another woman with a basket on her head can be seen to the right. Although these are also two women, the details of their bodies are not as defined as the women in the middle of the street. This gives a clear indicator that the two women that the title references are in the middle of the street.

Now that we know the title is referencing the two women in the street, we might start to ask ourselves, “are these two women friends”, “where are they going”, “do they know the man who is walking towards them”, “did Sekoto know these two women”, “what is the importance of these two women”? Furthermore, the title of the piece gives a clear focal point, the two women. This might make us think “easy, this piece is just about these two women, on to the next painting”. However, if we take into consideration Sekoto’s art practice and viewpoints, this painting and its title contains more depth and importance.

Sekoto created The Two Women while living in Paris. In Paris, he continued to create vibrant urban scenes from South Africa that featured black people. The location of The Two Women could be reminiscent of Sophiatown, a black neighborhood near Johannesburg. In 1939, Sekoto had moved to Sophiatown to “take part in the daily life of a big city and to see the human barriers”. Sophiatown was a diverse city. It had black and white residents and residents of Asian descent. Sekoto also noticed that Sophiatown contained different ethnic groups from various parts of Africa as well as many different Christian denominations.

According to Sekoto, “Tough, rough and squalid as the Sophiatown was, it opened to me for the first time in my life the joy of feeling no rigid barriers dividing people of different traditions and beliefs. I felt I was part of the whole, hence I could sing in bright colours – yellow, red, browns and blues – singing the sorrows, troubles and joys of those with whom I communicated.”

As stated earlier, Sekoto saw both the beauty and ugly in the scenes around him. Although being one of the many black South Africans who were greatly oppressed, Sekoto still held a great deal of optimism. Unfortunately, this oppression led to the start of the forced removal of Sophiatown’s colored population in 1955. Sophiatown would eventually be demolished and called Triomf meaning Triumph in Afrikaans. Years later, it would once again be renamed Sophiatown.

With this added knowledge, the title and the piece itself might look different to us. The title, The Two Women, truly reflects Sekoto’s optimism for the world. As someone who felt joy from the lack of barriers, the title projects the idea of no barriers. These are not two black or white women or two poor or rich women, they are just women not held back from any racial or social barriers. Sekoto’s optimism is not only seen through the title of this piece but also through its colors. Sekoto compared his use of colors (yellow, red, browns, and blues) to singing sorrows, troubles, and joys. His use of the words blues and singing could be a linkage to the popular music genre, The Blues. When we look at The Two Woman, we see Sekoto use the color blue to represent things such as clothing and trees. However, the majority of the scene is a mix of red, pink, and yellow showing how Sekoto is both portraying the sorrows of this scene through the blues but also the joys through the brighter colors.

References

David Adler, “Story of Cities #19: Johannesburg’s Apartheid Purge of Vibrant Sophiatown”. 2016.

Sekoto, Gerard. “A South African Artist.” Présence Africaine New Series, no.14/15 (June-Sept 1957)

Sekoto, Gerard. “Autobiography.” Présence Africaine New Series, no.69 (1st quarter 1969)

Explore other articles like this

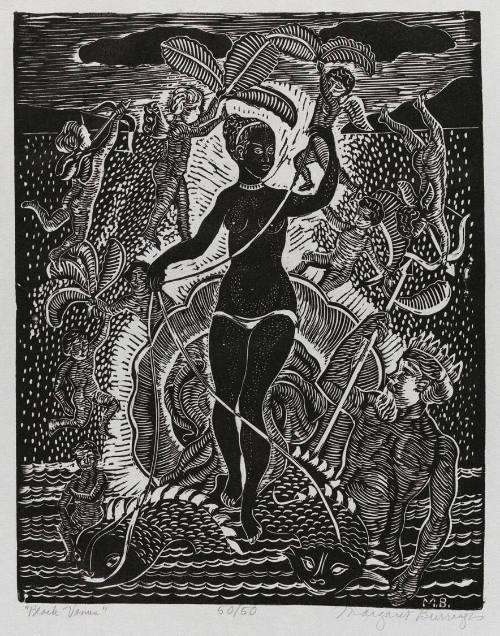

Diving into the Waters of The Black Venus

In her 1957 linoleum print, "Black Venus," Margaret Burroughs reimagines historical depictions of Black women, transforming narratives of exploitation into ones of resilience and empowerment. Her work challenges past portrayals and honors the Black female form.

The Andrew W. Mellon Fellowship: Now and Beyond

In this post, I will highlight some of the accomplishments of this project and address two main takeaways that can help those looking to reproduce a similar fellowship program.

Art Spotlight: The Abandoned Hut by Mordecai Buluma

In this blog post Angie and Tashae discuss the symbolism behind The Abandoned Hut by Mordecai Buluma as well as the conservation treatment used to prepare it for exhibition.