The Mystery of the Tasty Canvases

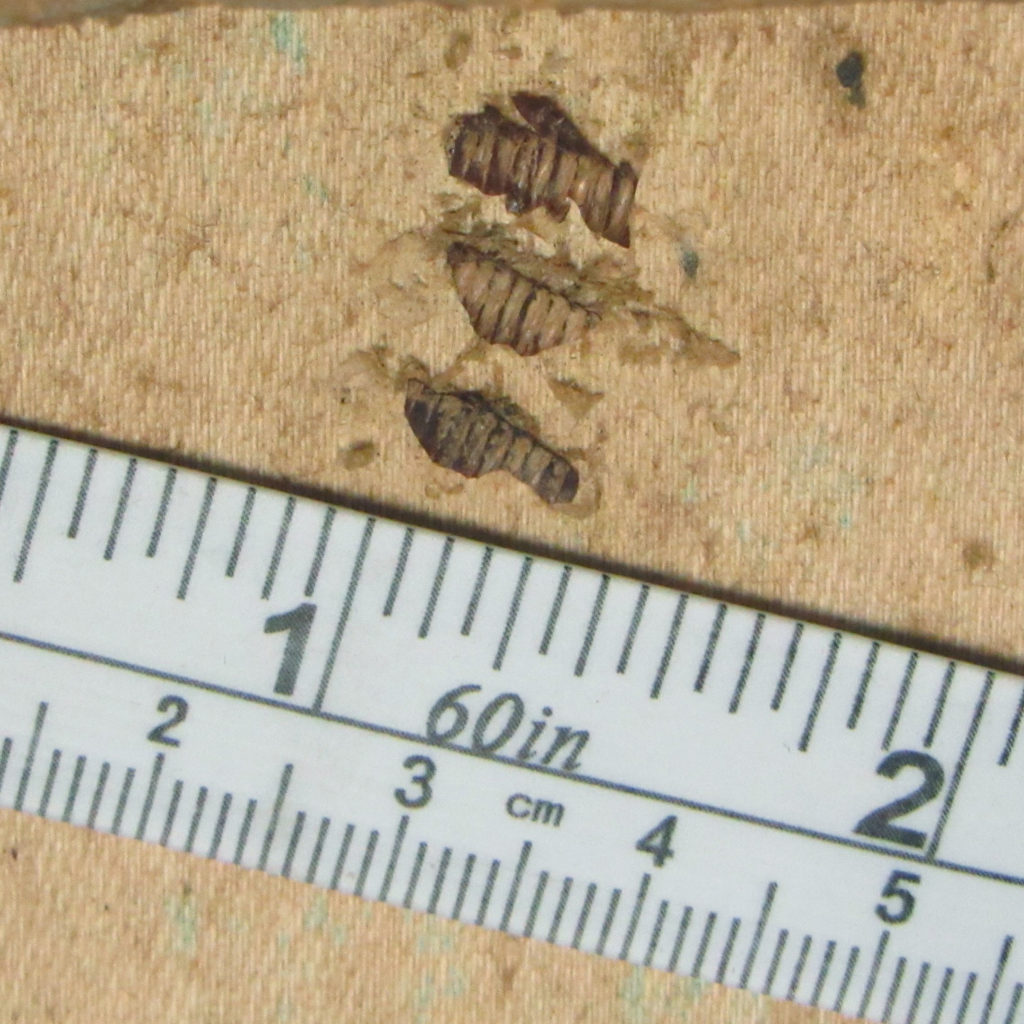

A small area where the canvas on the back of a painting has been eaten away, with insect casings nearby.

Introduction

Artworks can be negatively affected by many conditions or forces (see the blog post introducing the various Agents of Deterioration), but one of the most tricky to deal with are pests. This category encompasses all sorts of creatures, like rodents, birds, and insects, but the latter is what I will focus on, as there is evidence of some minor impacts that bugs have had on the Harmon Collection. Luckily, only very few of the artworks showed any signs of past insect infestation, and no current bug activity was found. This is very common in art and cultural heritage collections, especially anything containing organic materials. Read more below about how conservators deal with and try to prevent such attacks.

Signs of Pests

The first indication of pest infestation could be finding a live insect, which we did not come across in the Harmon Collection. Other times, dead insects or the skins they have shed are found, particularly between canvases and stretcher bars or frames. In the case of several contemporary African paintings by Akinola Lasekan, I found what appear to be remnants of insect casings adhered in one or several locations to the backs of the canvases. Sometimes, there was a patch of canvas nearby which appeared to have been eaten. We can distinguish this type of hole in a canvas from other sources of damage because the canvas fibers were not broken or torn, they are completely gone, revealing the back of the ground layer (see below).

Details of back of Traditional Alms Begging for Twins by Akinola Lasekan (Nigerian, 1916-1974), Mid-20th century, Oil on canvas, Gift of the Harmon Foundation, Hampton University Museum, 67.259

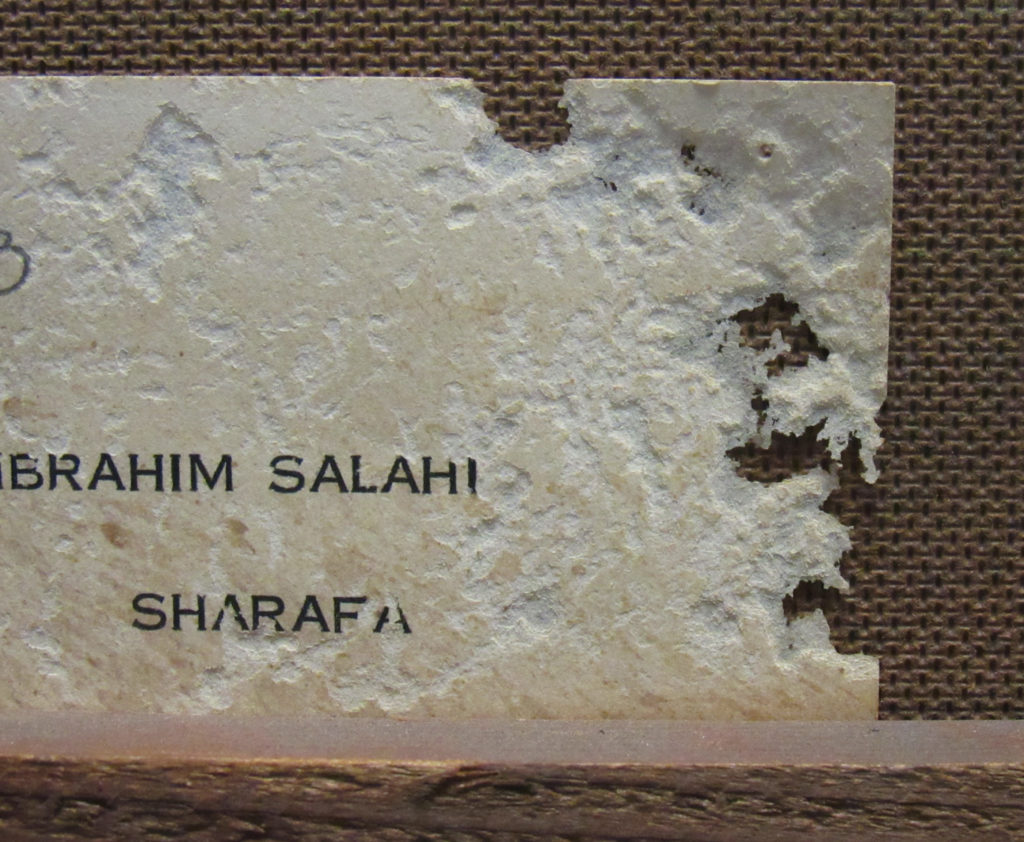

In another area on the back of the same painting, there were three fragments of insect casings, but no holes in the canvas (above at right). Below are examples of a paper label and a wooden carving which also have signs of past insects. The bugs have eaten through the layers of paper in characteristic patterns, which appear different from other types of damage. They often leave behind very thin layers of paper, as you can see at the right edge of the label below. In wood, they may also create tunnels just below the surface, leaving only a thin veneer of material on the outside. Or only their exit holes may be visible, and if these are light colored it is a sign that there could be current or recent activity. Luckily, all of these damages appear to have occurred long ago.

Left: Detail of back of Sharafa by Ibrahim El-Salahi (Sudanese, b.1930), Mid-20th century, Mixed media, Gift of the Harmon Foundation, Hampton University Museum, 67.361; Right: Detail of proper left side of Untitled (carved bust of a woman) by D.L.K. Nnachy (Nigerian, b. 1910), Mid-20th century, Wood, Gift of the Harmon Foundation, Hampton University Museum, 67.188

So why do insects and other pests attack art collections? Bugs generally do not eat oil-based paint or ground, which has no nutritional value to them, but they do tend to like plant- and animal-based materials, which is what canvases and paper labels are made of. Some creatures, like termites and powderpost beetles, love to eat wood. I wanted to determine what type of fibers were used to create Lasekan’s canvases, to see if there was a reason that I only found signs of insects on them, and not on other canvases. SoI took small fiber samples from the edges of the canvases and examined them under a microscope to identify the fibers present. I did not find wool as I had theorized, but instead the canvas seemed to be comprised mostly of cotton fibers. This could explain why the bug-eaten areas were all quite small, as the larvae could have tried out these materials, but quickly moved on to more suitable food sources.

Pest Identification

Next, I wanted to try to identify the species which had caused the damage, to better understand its life cycle, and keep an eye out for other forms of the pest. The website MuseumPests.net is an excellent resource to use for this process, as it has a searchable image library containing pictures of the various life stages of many different insects. It seemed to me that the Black Carpet Beetle larva pictured at right (from Jim Kalisch, UNL Entomology) closely resembled the segmented casing remains that I had encountered on the backs of the paintings.

Further research into this pest showed that though they are primarily attracted to animal based materials (wool, fur, felt, silk, feathers, etc), it is the larvae which graze on these materials as they grow and molt. The larvae can grow up to 5/16 of an inch and can live 6 to 12 months before pupating. The good news is that once the larvae pupate and become adults, they no longer eat the same materials, but prefer pollen and nectar for food, so they are generally found outdoors.

Prevention

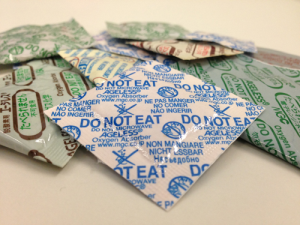

So how do conservators mitigate pest infestations and prevent them from happening or worsening? Mitigation is different than you might expect. The typical pesticides that you would use in a home or business are quite toxic and can be damaging to artworks, as residues are often left behind. So instead, conservators use safer but equally effective treatments like freezing, anoxia, or nitrogen chambers. Freezing an object with active bugs inside can be effective at killing them, if low enough temperatures are reached for a sufficient duration, but the cycle of thawing could lead to cracking of some materials, so it is not always the best choice. Anoxia involves creating a sealed container to fit the artwork, usually using a thick plastic or foil, and removing oxygen from it with “oxygen scavengers” (at left).

These are similar to what you find in some foods and shoe boxes, as they reduce moisture and extend shelf life of materials. This procedure requires careful calculations and monitoring throughout, to ensure that there are no leaks in the package. But after a few weeks, all of the insects should be dead, no matter what life stage they are in! Similarly, adding nitrogen to a sealed package can increase the speed of the process, and is more cost-effective for larger scale treatments.

It is difficult to recommend guaranteed ways to prevent pests from affecting collections at all. Their often very small size, ability to attach themselves unseen to clothing or boxes, and life cycles that include dormancy all make this agent of deterioration particularly insidious. Most institutions follow a policy of Integrated Pest Management, which involves using the most economical and least hazardous means of controlling pests proactively. Consistent monitoring is essential for early detection of any pests, especially in collections with lots of hair, wool, wood, or other organic materials. You can use pest traps like the one pictured below, which should be placed along the base of walls, to see if there is a common type of bug found in buildings or storage areas. Careful examination of any new items entering a collection, and isolating anything suspected of having pests are also important tactics. However, it is highly recommended that you hire an expert, such as a conservator focused on preventive care, to assess any areas or objects of concern.

References

Burke, John. “Anoxic Microenvironments: A Treatment For Pest Control”. National Park Service Conserv-O-Gram, Number 3/9, May 1999. Accessed February 6, 2023.

Child, R.E. “Monitoring Insect Pests With Sticky Traps”. National Park Service Conserv-O-Gram, Number 3/7, August 1998. Accessed February 6, 2023.

Maekawa, Shin and Kerstin Elert. The Use of Oxygen-Free Environments on the Control of Museum Insect Pests. The Getty Conservation Institute: Los Angeles, 2003.

“MuseumPests.net: Integrated Pest Management for Cultural Heritage”. Accessed February 6, 2023.

“Pests”. Science Museum of Minnesota. Accessed February 6, 2023.

Potter, Michael F. “Powderpost Beetles”. Entomology at the University of Kentucky. Revised June 2018. Accessed February 6, 2023.

“The Bookie Monster: attack of the creepy crawlies!” The British Library, Collection Care blog. Published August 27, 2013. Accessed February 6, 2023.

Explore other articles like this

Art Spotlight: The Abandoned Hut by Mordecai Buluma

In this blog post Angie and Tashae discuss the symbolism behind The Abandoned Hut by Mordecai Buluma as well as the conservation treatment used to prepare it for exhibition.

Tricky Tape and Finicky Frames

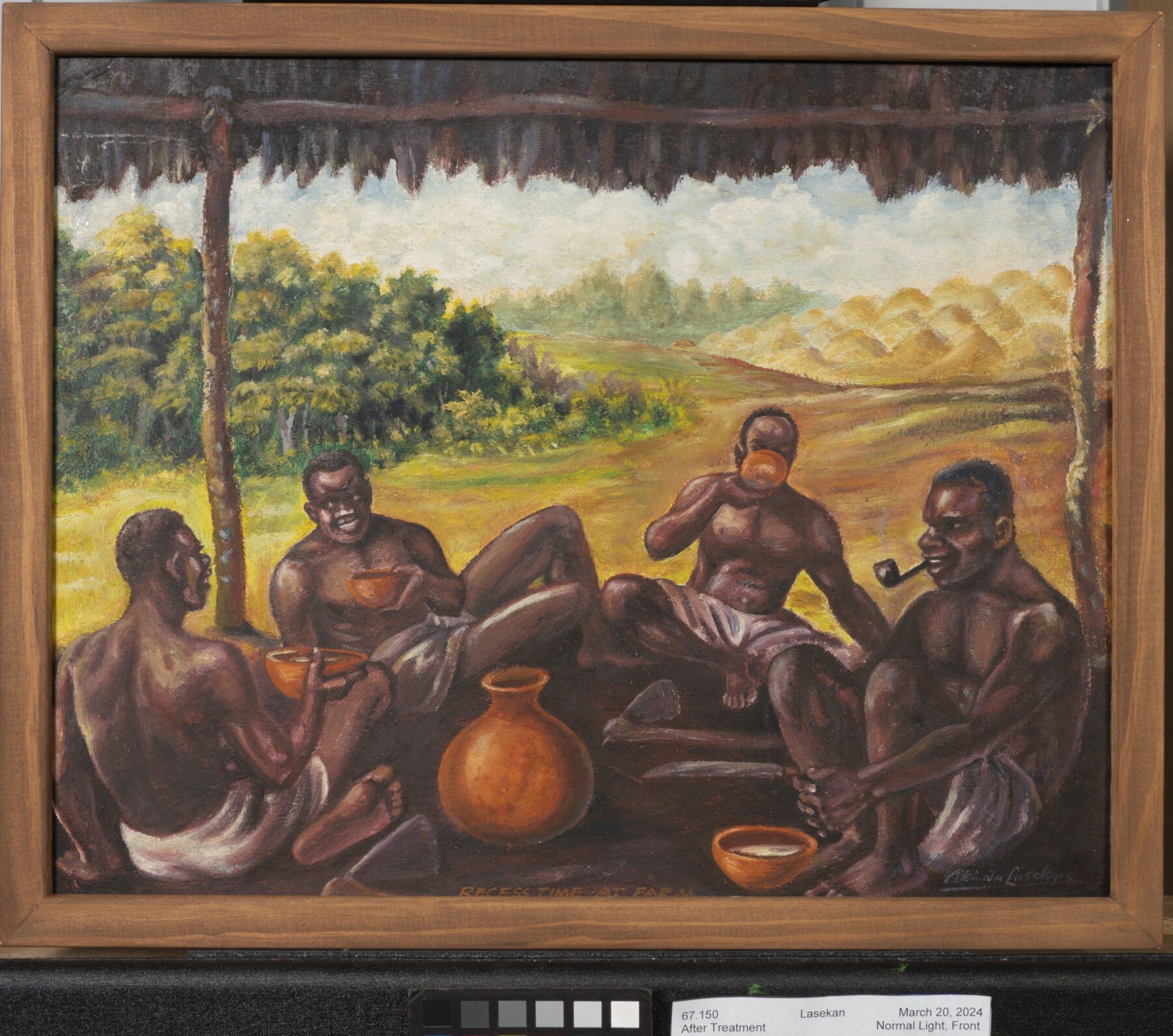

In conservation, tape can be tricky! This post discusses the conservation treatment of the painting Recess Time at Farm by Akinola Lasekan.

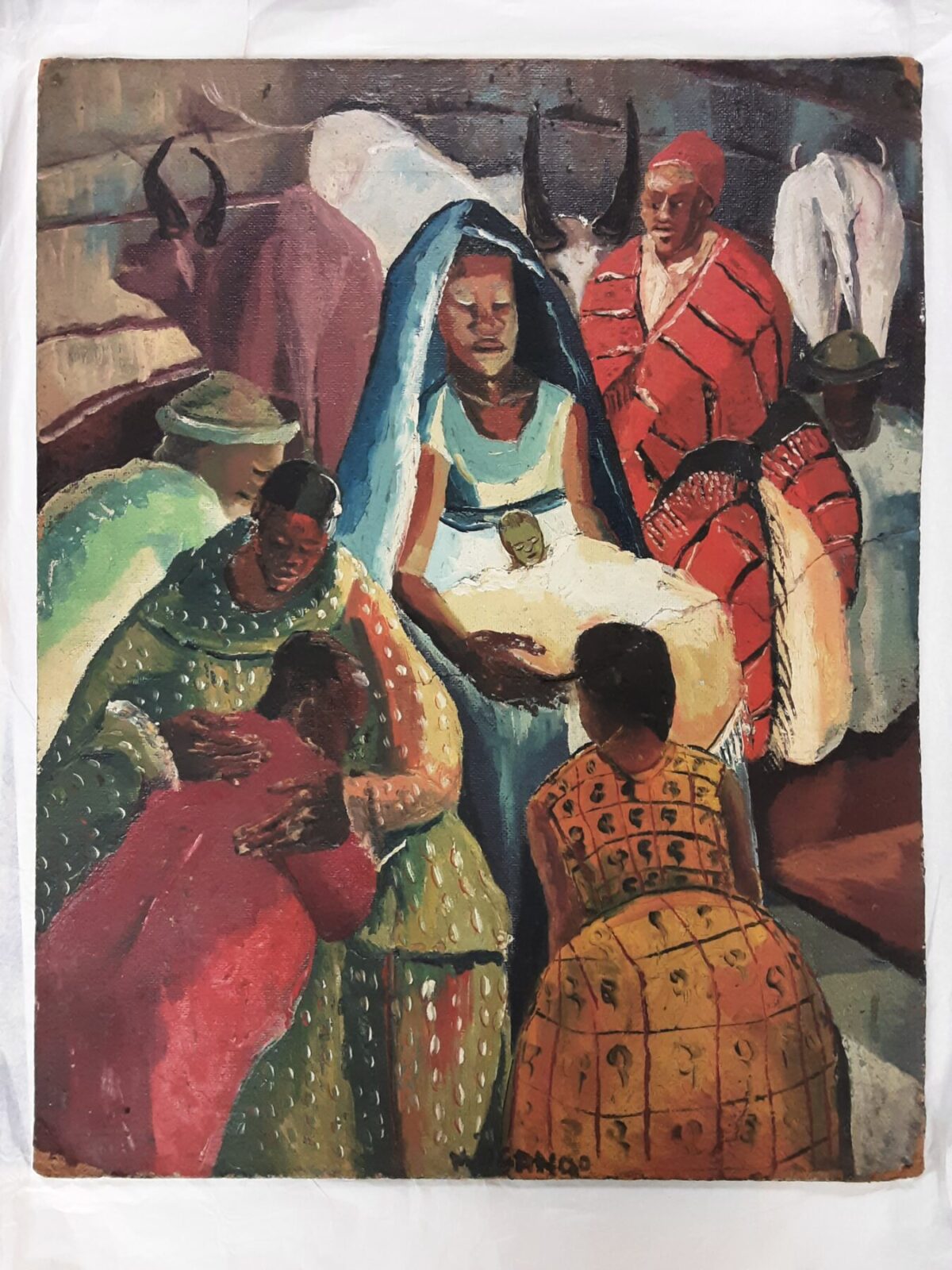

Christ in the Manger: Virginia’s Most Endangered Artifact?

"Christ in the Manger" by Francis Musangogwantamu, along with nine other selected artifacts from other institutions in Virginia, will be featured in an online public voting competition, which will take place from February 20th to March 3rd, 2024. The artifact that receives the most votes will receive the People’s Choice award and a $1,000 grant to be put towards the object’s conservation treatment.