Physical Forces and Inherent Vice

Conservation Fellow, Elizabeth Robson, working in Hampton University Museum's art storage.

The first Agent of Deterioration that I am going to cover is Physical Forces, combined with a related topic known as Inherent Vice. An important fact of art collections is that objects in storage do not stay “display-ready” indefinitely. There are many forces at work within and around them which can create or worsen condition issues as time passes, and create aesthetic concerns. Some of these have to do with the surrounding environmental conditions, some are related to forces coming from outside the work, and some are inherent conditions within the artwork. Conservators refer to the latter as elements of “inherent vice”, since they are things which have been a part of the artwork since it was created, and they often create challenges for the piece. Treating these conditions is tricky because conservators strive to respect the artist’s choices and intentions, but sometimes they have chosen difficult materials which resist preservation. So how do we respect those choices while still preserving the work for the future, ideally in a condition in which it can be shared and displayed?

In this post, I will explore the various types of cracking which can form in a painting, how to distinguish between them, and when to be concerned about them.

Traction Crackle vs. Mechanical Cracking

There are two kinds of cracks which can form in paintings over time, sometimes even when they are not disturbed. Traction crackle is caused by inherent vice in the paint layers, usually when lean paint (less medium) is layered over fatty paint (more medium). It is often not unstable or lifted, though it can be quite disruptive and disfiguring. On the other hand, mechanical cracks can also be created by inherent vices like underbound layers, or by physical forces like drops or blows to the support. These crack types can be differentiated by looking at certain features to try to determine their origin, and help decide whether the painting requires immediate stabilization treatment.

How to Identify Crack Types

Traction Crackle

Traction crackle may appear like spread out or broad cracks, which reveal the layer(s) below. The underlying layers may be shiny due to a greater amount of media present. It is usually not recommended to treat this type of cracking, since it is indicative of the artist’s working process and is usually stable. However, particularly disruptive cracks which are detrimental to the aesthetics of the work could be inpainted (retouched without covering any original paint) using stable, reversible materials if it was desired by the owner.

For example, it appears that Elimo Njau layered lean paint over fatty paint which was not fully cured, leading to the crack patterns seen in the painting below.

Details of Head of a Man by Elimo Njau (Tanzanian, b. 1932), Mid-20th century, Oil on Masonite, Gift of the Harmon Foundation, Hampton University Museum, 67.117

Even if the lower layers are not shiny, they may have the appearance of alligator skin, which is why this condition is sometimes called “alligatoring”. This can be seen in several places within Lasekan’s painting Preparing Food at left.

Details of Preparing Food by Akinola Lasekan (Nigerian, 1916-1974), Mid-20th century, Oil on canvas, Gift of the Harmon Foundation, Hampton University Museum, 67.262

Mechanical Cracking

Outside physical forces, like strikes to the support, may create mechanical cracking of the paint, though this is not always apparent at first when smaller blows occur. When the canvas or board support becomes deformed, this will likely lead to cracks in the paint layer, seen below at left. Even if the action does not puncture or break the support, it may create underlying insecurities within the paint or ground, which eventually become visible on the surface over time, seen below at right.

Left: Detail of Waiting for Fishermen by Akinola Lasekan (Nigerian, 1916-1974), Mid-20th century, Oil on canvas, Gift of the Harmon Foundation, Hampton University Museum, 67.148; Right: Detail of The Moon and the Valiant by Alexander “Skunder” Boghossian (Ethiopian, 1937-2003), Mid-20th century, Paint on canvas, Gift of the Harmon Foundation, Hampton University Museum, 67.325

Inherent vice within the layers may also lead to mechanical cracking over time, which may become apparent with or without outside forces. This is the most insecure and potentially damaging condition to look out for. If any of the layers of a painting do not have sufficient adhesion or are underbound, this can lead to lifting and delamination of the paint layer(s), seen below at left. This may also happen when new layers of paint are added on top of a completed painting, which may be varnished or have dust on the surface, seen below at right. Due to the intervening materials, the layers may not adhere together very well, and can crack and separate over time. Blind cleavage is a condition where the paint has separated, but there is no visible crack on the surface yet, which is harder to identify and can be equally damaging. Loose paint can be easily dislodged from the surface and lost when the painting is moved. In cases like this, it is important to avoid touching these areas, store the painting flat, and contact a conservator for further assessment and examination.

Left: Detail of Wedding Feast by Sam Joseph Ntiro (Tanzanian, 1923-1993), Mid-20th century, Oil on canvas, Gift of the Harmon Foundation, Hampton University Museum, 67.388; Right: Detail of Asoba (A Game in Ghana) by Emmanuel Owusu Dartey (Ghanaian, 1927-2018), Mid-20th century, Oil on canvas, Gift of the Harmon Foundation, Hampton University Museum, 67.107

Activity!

The following painting, Image #3 by Ibrahim El-Salahi, contains both types of cracking. Can you tell which picture shows the traction crackle and which shows mechanical cracking? (answer below)

How to Prevent These Conditions

Unfortunately, once the art has been created, there is not much that can be done to stop the effects of the inherent vices and natural aging processes taking place. However, artists can keep in mind the adage of “fat over lean”, which dictates the use of lean layers first (less medium), followed by layers with successively more medium, ideally letting each layer fully dry before continuing. It is important to note that the inherent vices found in many paintings are not always the artist’s fault. Manufacturers, especially in the mid-20th century, were experimenting with paint compositions, making modern oil paints less stable than traditional oil paint due to the various additives and ratios of materials (Izzo et al). This created new difficulties in the curing process, which were unknown at the time of their use by many artists.

Once a painting has been damaged by a blow or even a touch, these physical forces cannot be reversed, but maintaining appropriate environmental conditions may prevent any cracks from becoming apparent or worsening. This includes avoiding rapid changes in temperature and relative humidity, which will be further discussed in future posts, and moving the artwork as little as possible. If the painting is on a canvas support, it can be protected from the back with the addition of a backing board, which will also help stabilize the climatic conditions. Backing boards should be made of archival materials, secured to the frame or stretcher, and applied under the supervision or advice of a conservator.

Answer for Image #3 by Ibrahim El-Salahi: The image on the left shows mechanical cracking, which occurred along the edge of the stretcher bar as a result of a blow to the canvas. The image on the right shows traction crackle, where the paint has opened up laterally while drying, revealing the lighter colored ground below.

References

“Cleavage.” AIC Wiki, American Institute for Conservation, 26 April 2021.

“Crackle.” AIC Wiki, American Institute for Conservation, 10 September 2021.

“Inherent vice.” AIC Wiki, American Institute for Conservation, 26 April 2021.

Izzo, Francesca Caterina, et al. “Modern Oil Paints – Formulations, Organic Additives and Degradation: Some Case Studies”. Issues in Contemporary Oil Paint, edited by Klaas Jan van den Berg, et al., Springer, 2014, pp. 75-104.

Explore other articles like this

Art Spotlight: The Abandoned Hut by Mordecai Buluma

In this blog post Angie and Tashae discuss the symbolism behind The Abandoned Hut by Mordecai Buluma as well as the conservation treatment used to prepare it for exhibition.

Tricky Tape and Finicky Frames

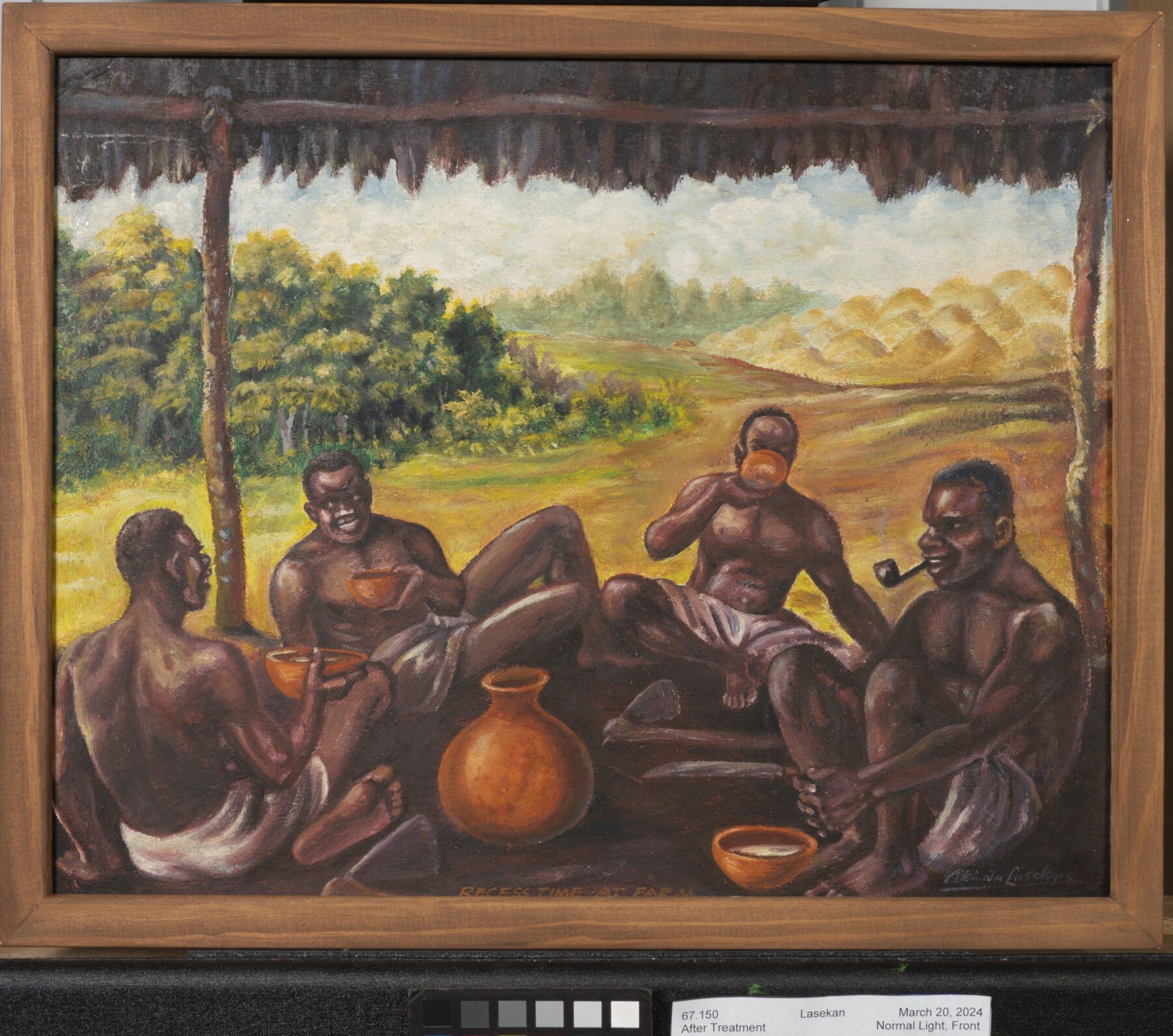

In conservation, tape can be tricky! This post discusses the conservation treatment of the painting Recess Time at Farm by Akinola Lasekan.

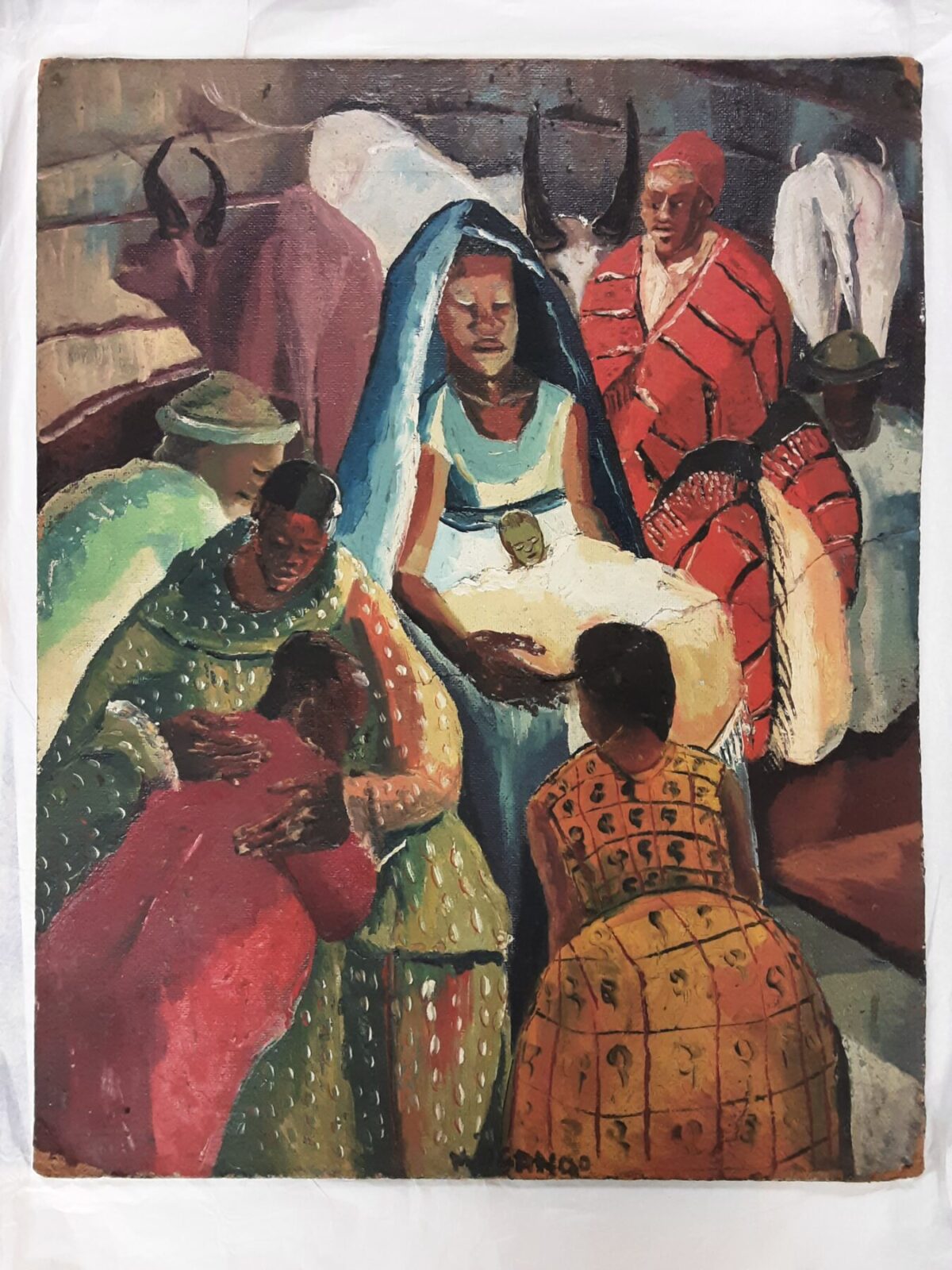

Christ in the Manger: Virginia’s Most Endangered Artifact?

"Christ in the Manger" by Francis Musangogwantamu, along with nine other selected artifacts from other institutions in Virginia, will be featured in an online public voting competition, which will take place from February 20th to March 3rd, 2024. The artifact that receives the most votes will receive the People’s Choice award and a $1,000 grant to be put towards the object’s conservation treatment.