Diving into the Waters of The Black Venus

It is fascinating to study how a community of people who are dispersed yet interlinked by their African ancestry express their unique experiences through art. As a history major, uncovering the background of the artwork Black Venus was shocking. While learning about this print and its creator, I was inspired to give printmaking a try. The hands-on experience deepened my appreciation for the work by artist Margaret Burroughs, whose creativity was influential and intertwined with her activism. She was a key part of the Chicago Black Renaissance Movement. Born in Louisiana around 1915-17, Margaret Taylor Goss Burroughs became involved in her community at an early age. A creative activist, writer, and educator, Burroughs focused on preserving black history and art through establishing institutions and producing educational materials. In February of 1961, she established the Ebony Museum of Negro History and Art, later renamed the DuSable Black History Museum and Education Center. Additionally, Margaret Burroughs established the South Side Community Arts Center. Her achievements would continue to cultivate the art scene of the Bronzeville community in Chicago.

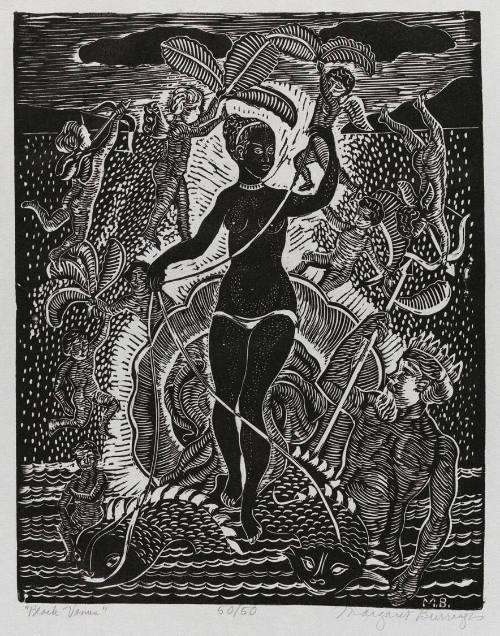

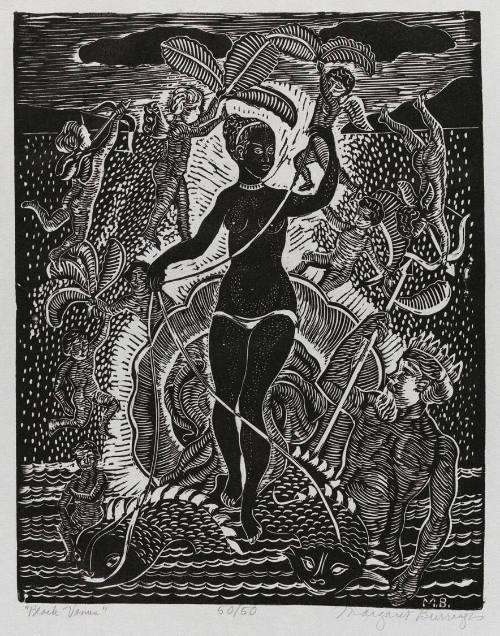

When viewing Burrough’s Black Venus, I thought about the underlying activism of her subject choice. Race relations in the United States are constantly under pressure, infiltrating heavily consumed media and pushing discouraging narratives. Margaret Burroughs exercised what I would call artistic innovation, creating new lenses of positive representation by transforming initially disparaging concepts. In 1957, Magaret Burroughs created Black Venus, a linoleum print that initially presents itself as an interpretation of Sandro Botticelli’s The Birth Of Venus. However, when conducting a close inspection, there are not many similarities between the two. Rather, they both were created during Renaissance periods. Botticelli witnessed the challenge of religious authority, straying away from the themes surrounding Christianity, and instead creating depictions of mythical Roman Icons. Margaret Burroughs challenged the portrayal of black identities in U.S. history, bringing forth truths that were commonly disregarded. Her print, Black Venus, visually parallels an image created by Thomas Stothard, engraved by William Grainger called Voyage of the Sable Venus from Angola to the West Indies. Stothard’s design has elements inspired by Venus the roman Goddess of love. A seemingly beautiful portrayal of a black woman, yet with problematic connotations.

The Voyage of the Sable Venus from Angola to the West Indies is a visual representation of the 18th-century poem, The Sable Venus: An Ode, found in Bryan Edward’s History, Civil, and Commercial of the British Colonies in the West Indies. All layers of corresponding literature conclude with support of British intervention and slavery. Both the poem and illustration discuss black beauty, a controversial topic when compared to the Western standards of beauty. This is a historically complex discussion topic, as beauty should be celebrated, yet it is commonly defined by superficial concepts that promote exclusionary standards. The image and poem come from a place of ingrained fetishization of the black female body by white in power, and that alone leaves a lot to be unpacked. The evidence of sexual exploitation of black woman lies within history, Sally Hemmings was exploited by her enslaver, Thomas Jefferson. Louisa Piquet was young when she, too, was exploited. Numerous enslaved women were victims of their oppressor’s lust.

Instead of ending the story of the Black Venus with exploitation, Margaret Burroughs chooses resilience. Unlike the image created by Thomas Stothard, Burrough’s image removes the British flag, and the initial title, detaching the movement from Angola to the West Indies entirely. Instead of primarily focusing on enslavement, Burroughs focuses on paying homage to the black female body.

Her skills with the linoleum method of printmaking grew with the guidance of Leopoldo Mendez. Like Burroughs, Mendez was an educator, artist, and activist. Printmaking, for him, was a platform to express messages surrounding the political and social climate of the Mexican Revolution. Printmaking was his vehicle to amplify the voices of the oppressed, educate the masses, and challenge the pillars of society. This approach would travel back to Chicago with Burroughs, illuminating the way for more activism.

Despite technological advancements, can printmaking still be a substantial vehicle for advocacy in the 21st century? The answer is yes! An application of advocacy through printmaking that grabbed my attention was the creation of Zines. This terminology derives from fan magazines, which are small publications where creative freedom is entirely up to the creator or creative collective. Independent authors and groups can express their interests, opinions, imagery, and more. Initially created to disperse information on different fandoms in the early 20th century, this concept returned in different forms throughout history. Little magazines were created and dispersed during the Harlem Renaissance to share black literary works. In the late 20th century, countercultural groups like Riot Grrrl produced feminist literature and influential visuals. Like Margaret Burroughs and the previous revolutionary examples, anyone can use printmaking as a form of advocacy amongst their community and beyond.

Experimenting with Printmaking

I had to try a little experiment to see if I could produce prints. Before jumping in, I wanted to practice so instead of using linoleum I used a rubber block piece. With guidance from Angie, the Andrew W. Mellon Conservation Fellow, we identified that the key to creating a good design is to carefully carve away the excess leaving your design raised. I chose to draw a Coneflower (Rudbeckia) and a Ginko tree leaf (Ginkgo biloba), as they both turn yellow during their lifetimes. Yellow has grown on me over the years and it was the color of my childhood bedroom. Yellow is the light at the end of the tunnel and is often associated with the sun. I encourage anyone to try this at home. There are multiple ways to create prints with materials around your house like large erasers, a cost-effective alternative. Let those creative ideas grow.

Explore other articles like this

Consolidating Miranda “Olayinka” Burney-Nicol’s Night Dancer

This post introduces Angie Lopez, the current Andrew W. Mellon Conservation Fellow, and shares her journey into the art conservation field. She also discusses her experience of working on her first painting from the Hampton University Modern African Art collection, Night Dancer by Miranda “Olayinka” Burney-Nicol, and her examination of the painting's structure, artist’s technique, and condition.

Discussion on the Painting Grief by Afi Ekong

NEH fellow in paintings conservation, Katie Rovito, and Andrew W. Mellon curatorial fellow, Tashae Smith, sat down to discuss the Modern Nigerian artist, Afi Ekong and the conservation of her painting Grief.

Mending Tears in Afi Ekong’s Grief

This post goes in-depth on the conservation treatment of the painting Grief by Afi Ekong. Treatment was completed by Katie Rovito, National Endowment for the Humanities Conservation Fellow at the Chrysler Museum of Art. Learn how Katie tackled this treatment, including how she mended tears and inpainted.