Biggers and Boghossian: A Diasporic Voyage to Cultural Consciousness

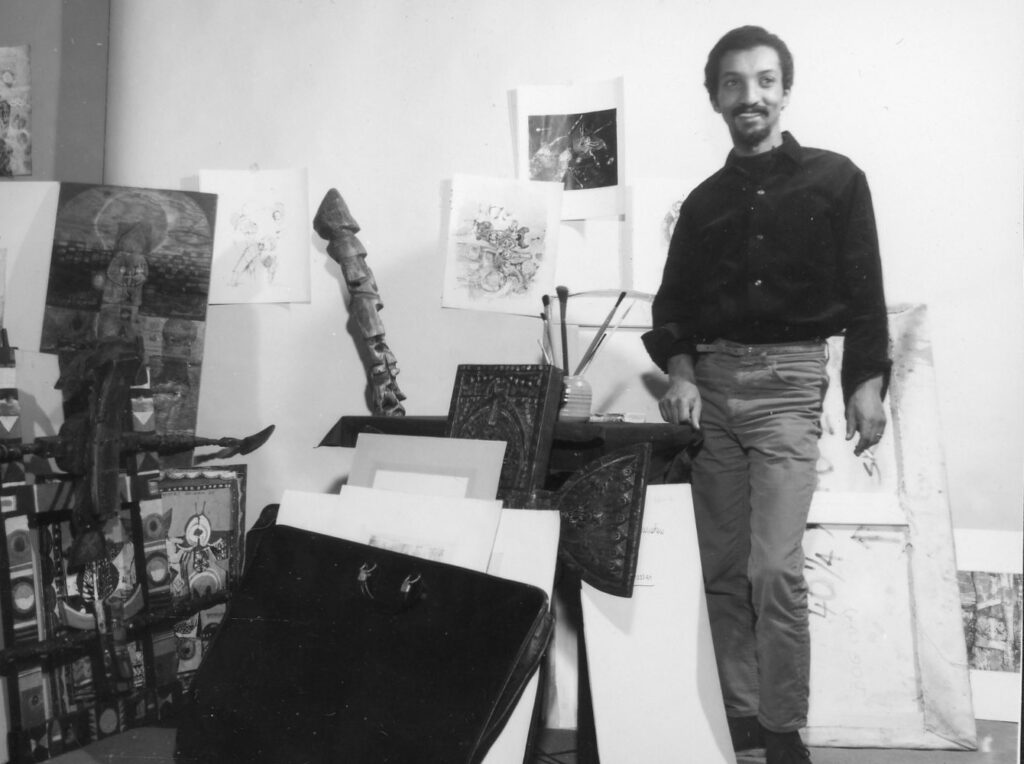

Photographer unknown, Boghossian posing behind a table in front of some of his artworks, including The Union, 1964 (bottom right), which is in the collection of Hampton University Museum. From National Archives and Records Administration, Hampton Foundation Collection, 1922–1967.

This is an excerpt from an upcoming catalogue for the exhibitions Sankofa: Constructing Modern African Art and I Am Copying Nobody: The Art and Political Cartoons of Akinola Lasekan. You can learn more about the upcoming exhibitionsHERE.

Boghossian’s Early Works in Paris

From 1957 to 1963, Alexander “Skunder” Boghossian created figurative artworks in Paris that drew inspiration from his Ethiopian heritage. Some of these pieces were featured in the Harmon Foundation’s unprecedented exhibition Art from Africa of Our Time. Held at the New York offices of the Phelps- Stokes Fund from December 1961 to January 1962, the exhibition showcased the work of forty-five artists from fourteen African countries.[i] Boghossian’s contributions included Young Girl in Red (oil on canvas), Le Marche (oil on canvas), The Market Place (watercolor), and The Guitar (watercolor), the last of which is in the Hampton University Museum collection. The Guitar is an exemplary illustration of Boghossian’s figurative work that tapped into Ethiopian culture. This piece depicts a musician seated at a black rectangular table within an illuminated orange and green room. The figure’s elongated neck and triangular-shaped head face the viewer, but the eyes reveal a preoccupation with something to the right. The musician’s instrument is a six-stringed Krar, commonly found in Ethiopia and Eritrea.

Three Spheres of Influence

Three spheres influenced Boghossian’s journey toward cultural consciousness and his adaption of a new art style that moved from figurative portraits and landscapes to abstract depictions of spirituality, life, and death. The first was his exposure to African art during his daily visits to the Musée de l’Homme. For two years, Boghossian studied the forms and cultural significances of the African sculptures and masks at the museum. These visits had a profound impact on him, as he noted, “African art created a condition in my mind. … I learned that creation must be an immense and unceasing modulation of concept.”[ii] His newfound knowledge on African art and culture allowed him to develop aesthetic choices that would shape his work for years to come.

The second sphere was his exchanges with Black intellectuals and writers, such as Aimé Césaire, one of the founders of the Negritude movement, and Cheikh Anta Diop, a scholar whose work supported the decolonizing and revaluing of African historical narrative. From their conversations and works, Boghossian came in contact with Negritude and Pan-Africanism. These movements offered the promotion of African unity among the Black diaspora and the rehabilitating view of African culture, which gave Boghossian the creative tools to honor and uplift other Black diasporic cultures and experiences in his art.

The third sphere was his interaction with other African artists who were honing their artistic practices in Paris, particularly the Ivorian sculptor Christian Lattier, who invented an artistic style that involved large, three-dimensional figures formed by stringing fiber around a frame.[iii] Lattier’s ability to merge the supernatural into his artworks was significant for Boghossian, as was his belief in powerful but invisible spirits. Like Lattier, Boghossian would struggle with his own complicated relationship with the spirits and would grapple with this in his work.[iv]

The Nourisher Series (1963–64)

Boghossian’s Nourisher Series is where the influences of these three spheres can first be seen. This series displays Boghossian’s growing fascination with life, death, and fertility and their interplay in the visible and invisible realms. The mellow color palette is punctuated with abstracted skeletal and insect-like forms, as well as African-like masks, a nod to Boghossian’s study of African art forms at Musée de l’Homme.[x] According to Elizabeth W. Giorgis, the Nourisher Series contains twelve artworks but only two are photographed, while nine are unaccounted for. One work in the series, X-ray Nourishers, can be found at the Hampton University Museum. The painting features two seated figures with mask-like faces, stripped of their flesh to reveal abstracted bones and organs. The title of this work implies we are seeing the underlying essence of these figures who are reduced to their fundamental purpose: nourishing, a vital need for sustaining life. This piece also includes smaller, ghostly figures with mask-like faces, a motif Boghossian would continue to explore in his work.

[i] Harmon Foundation, Inc., Art From Africa of Our Time (New York: Aalborg-Tulane Printing Company, 1962). Skunder

Boghossian, Ethiopian Painter (New York: Harmon Foundation, Inc., 1965). The Harmon Foundation started to feature Boghossian’s works in 1961, starting with their sponsored group exhibition at Hampton Institute, now Hampton University.

[ii] Skunder Boghossian, Ethiopian Painter.

[iii] Monica Blackmun Visonà, “Lagoon Artists in a Global Context,” in Constructing African Art Histories for the Lagoons of Côte d’Ivoire (New York: Routledge, 2017), 169.

[iv] Elizabeth W. Giorgis, “The Modernists of the 1960s: GebreKristos Desta and Skunder Boghossian and Their Students,” in Modernist Art in Ethiopia (Athens: Ohio University Press, 2019), 142.

[v] Salah M. Hassan, “Alexander ‘Skunder’ Boghossian,” in To Conserve a Legacy: American Art from Historically Black Colleges and Universities (Andover: Addison Gallery of American Art, 1999), 179.

Explore other articles like this

The Andrew W. Mellon Fellowship: Now and Beyond

In this post, I will highlight some of the accomplishments of this project and address two main takeaways that can help those looking to reproduce a similar fellowship program.

Art Spotlight: The Abandoned Hut by Mordecai Buluma

In this blog post Angie and Tashae discuss the symbolism behind The Abandoned Hut by Mordecai Buluma as well as the conservation treatment used to prepare it for exhibition.

Opening of I am Copying Nobody the Art and Political Cartoons of Akinola Lasekan

On April 13, 2024, I Am Copying Nobody: The Art and Political Cartoons of Akinola Lasekan opened at the Chrysler Museum of Art. Here are some highlights from the exhibition.