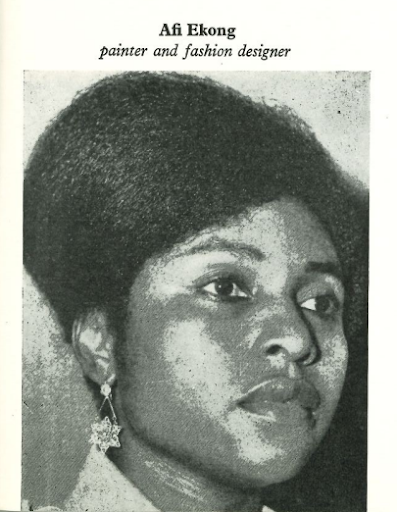

Artist Talk: Grief by Chief Lady Constance Afiong Ekong

For my first post of the Artist Talk series, I will be sharing information on the prolific artist Chief Lady Constance Afiong Ekong, also known as Afi Ekong. Along with being a pioneer of Modern Nigerian and African art, she was an art collector, fashion designer, jewelry maker, and entrepreneur. Ekong was a present and influential figure in the Nigerian art scene until her death in 2009. Although we can not talk with Ekong, we can still have a conversation with her paintings. Today we will be in conversation with Ekong’s painting, Grief, which can be found in the Harmon Foundation Modern African Art collection located at Hampton University Museum.

*The Artist Talk series is meant to share information on a specific artist. Most of the artists we will “talk” with have passed away. Although we cannot talk to the artist directly, we can still have a conversation with their art.

Who is Chief Lady Constance Afiong Ekong?

Afi Ekong was born in Duke Town, Calabar, Nigeria on June 26, 1930. She was born into the royal house of the Obong of Calabar. Her professional art training began at Oxford City Technical School (1951-1953), where she trained as a painter and fashion designer. In 1955, she attended St Martin’s School of Fine Arts and later studied history of costumes at the Central School of Arts, which she completed in 1957. Ekong’s art training in England made her one of the first generation of Nigerian artists to receive their training abroad. Other firsts for Ekong include: being the first female artist in Nigeria to be academically trained and the first female artist to exhibit in Nigeria.

In the 1960s, Ekong became an executive board member and art manager of the Lagos Art Council and supervisor of Gallery Labac (Lagos Branch of the Art Council). In order to grow interest in art and showcase the art of other Nigerian artists, Ekong created Cultural Heritage, a weekly television program. She used her platform to broadcast the works of artists such as Yusuf Grillo, Solomon Wangboje, Uche Okeke and Simon Okeke. By 1966, she had opened The Bronze Gallery, the first private art gallery in Nigeria. Due to her work of promoting art and women’s education in West Africa, she was awarded “The Star of Dame Official of the Human Order of African Redemption” in 1962 by the former President of Liberia, William Tubman. Ekong’s work of improving the lives of women continued into the 1980s when she became the Chairman for the International Council of Women Standing Committee. In 1994, she opened The Bronze Gallery in Fiekong Estate which showcased not only her art to the public but the art of other Nigerian artists.

Exhibitions and Art Style

Afi Ekong was the first female artist to have a solo exhibition in Nigeria. Her solo exhibition was held at the Exhibition Centre during the Lagos Festival of Arts in 1958. In 1961, she had another solo exhibition titled Afi Ekong at Galeria Galatea in Buenos Aires, Argentina. Group exhibitions that have included Ekong’s work are, Art from Africa of Our Time, Phelps-Stokes Fund (1962); First World Festival of Negro Arts (1966); and Women Now, National Gallery of Crafts and Design (1990). Examples of Ekong’s work shows her versatility when it comes to her use of color, subject matter, and technique.

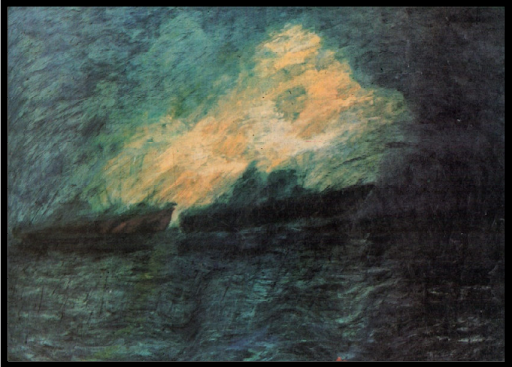

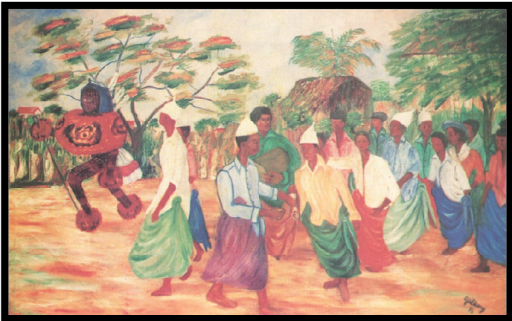

Ekong painted landscapes as seen through her 1988 painting, Before the Storm, Atlantic View from Lagos. Here, Ekong uses dark and muted colors to depict two boats being engulfed by a storm. Ekong’s contrast of light and dark colors evokes the feeling of being consumed by a dark entity. In her 1996 painting, Ekpe Dancers we get a more vibrant scene. Ekong is most likely depicting an Ekpe Masquerader and dancers from her own ethnic group, the Efik. Despite being a devout Christian and ordained Elder in the Presbyterian Church, her attachment to her ethnic and cultural identity is on full display in Ekpe Dancers. Ekong also painted subjects outside of her own ethnic group as seen through the painting Two Yoruba Ladies (Sisi Eko), 1993. In this painting, Ekong uses subtle colors to capture the beauty and elegance of the two women.

A Conversation with Grief

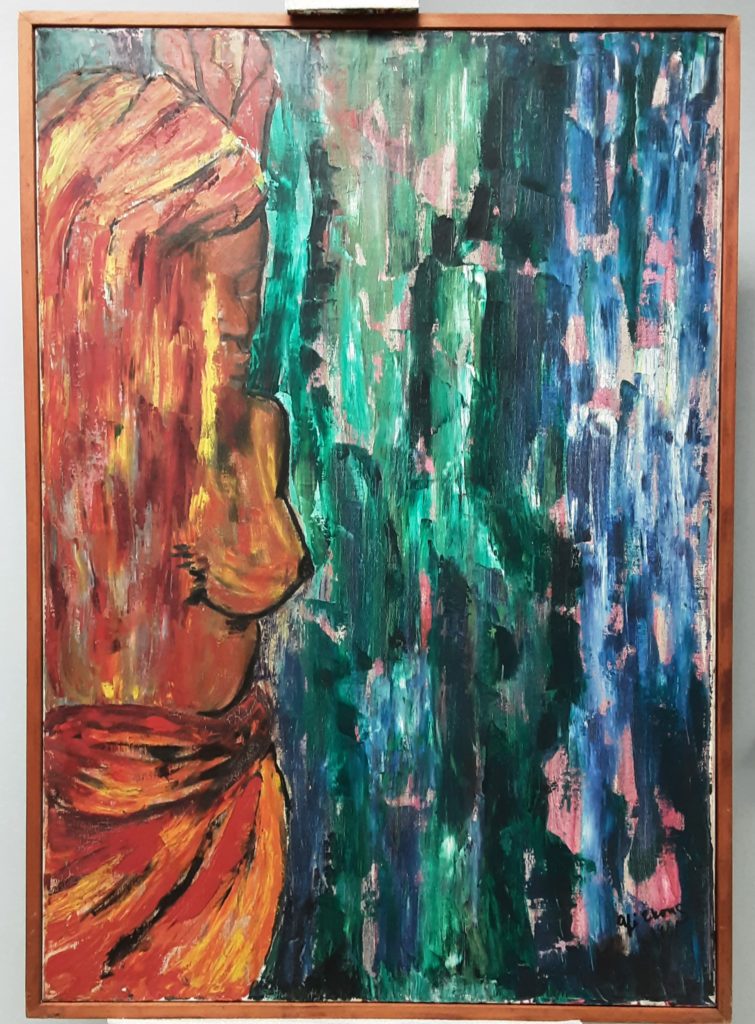

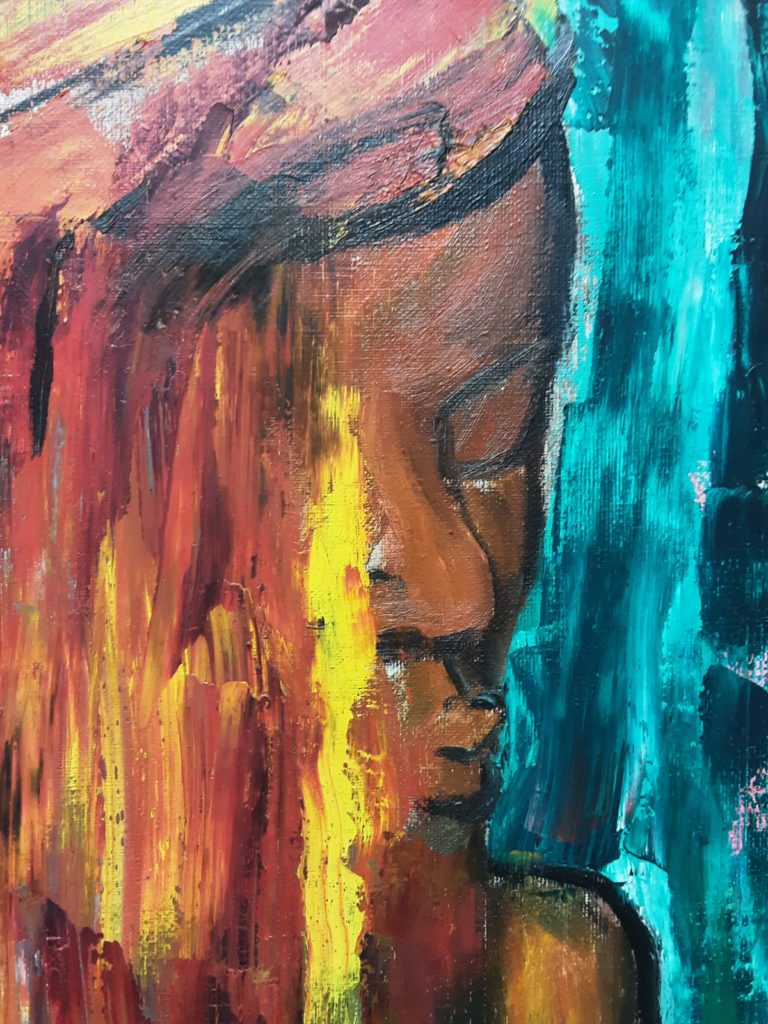

At a considerable height of 40 9/16 inches and a width of 28 13/16 inches, Grief depicts a woman with her eyes closed and head slightly tilted down. One of her breasts is exposed while the other is concealed by a waterfall of reds, oranges, and yellows. This coloring continues to the rest of the woman’s body and clothing. The woman’s large fiery body automatically draws the viewer’s attention, especially considering its juxtaposition with the cooler background colors of blue and green. Although the thick blue and green lines take up much of the canvas, pink and exposed canvas can be seen underneath the blues and greens.

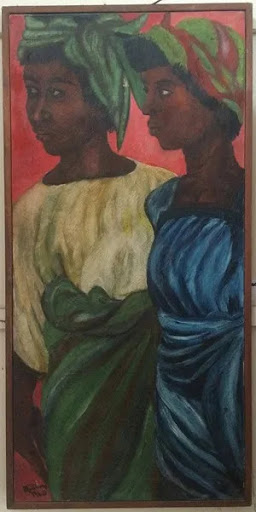

Questions we might have about the painting are “who is this woman and what is her grief”? By looking at Ekong’s other 1961 oil painting, Fadeke and Ada, we might be able to come to a conclusion on who this woman is and what is her grief.

In the painting Fadeke and Ada, Ekong uses a richer pink for her background which is different from the lighter pink color used in the background of Grief. However, she uses similar blues and greens in the clothing of the two women. Assuming that Fadeke and Ada were real people, Ekong was painting the two women how she saw them. Beautiful and well dressed brown women who are larger than life and deserve to take up all the space of her canvas. This is drastically different from the woman in Grief whose body does take up the height of the canvas but is tucked away to the left. While Fadeke and Ada resemble real people, the woman in Grief resembles more of an idea or the embodiment of grief. We can argue that the woman is not just experiencing grief but she is actually grief. We usually associate dark colors with grief such as black at funerals. Ekong has gone in the opposite direction by using fiery colors to depict grief as an emotion that is consuming and quick-spreading like fire. Ekong allows us to see grief how she might have seen it. An emotion of solitude, seen through the lone woman left to one side of the painting but also a raging emotion, seen through the depiction of a woman consumed by the colors of fire.

Chief Lady Constance Afiong Ekong is a pioneer of modern Nigerian and African art. Apart from being among the first generation of Nigerian artists to receive their training abroad, Ekong was also the first female artist to exhibit in Nigeria. Ekong contributed to the growth of Nigerian art by creating Cultural Heritage, a weekly television program that broadcasted the works of Nigerian artists, and through the creation of The Bronze Gallery, the first private art gallery in Nigeria. Outside of the art world, Ekong continued her work for the improvement of women’s lives as Chairman for the International Council of Women Standing Committee. Despite passing away in 2009, Ekong leaves her legacy in the artists she helped and those who they helped. Her legacy also continues through her art at The Bronze Gallery in Fiekong Estate and other museums and galleries around the world.

References

Afi Ekong: Pioneer of Modern Nigerian Art, 2019, Artwa.Africa: Art in Africa

Ecoma, Victor E., “Chief Lady Afi Ekong in the Art Historical Account of Modern Nigerian Art”, Research on Humanities and Social Sciences, 3 (6).

Kelly, Bernice M., Stanley, Janet L.,Nigerian Artists: A Who’s Who and Bibliography. Hans Zell Publishers, 1993.186.

Nigeria Magazine, “Our Authors and Performing Artists”. 89. June 1966. 135.

Okeke-Agulu, Chika. Postcolonial Modernism: Art and Decolonization in Twentieth-Century Nigeria. Duke University Press, 2015. 231.

Explore other articles like this

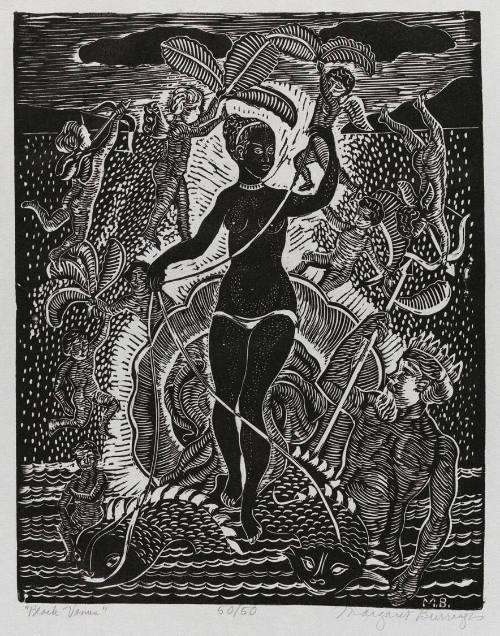

Diving into the Waters of The Black Venus

In her 1957 linoleum print, "Black Venus," Margaret Burroughs reimagines historical depictions of Black women, transforming narratives of exploitation into ones of resilience and empowerment. Her work challenges past portrayals and honors the Black female form.

The Andrew W. Mellon Fellowship: Now and Beyond

In this post, I will highlight some of the accomplishments of this project and address two main takeaways that can help those looking to reproduce a similar fellowship program.

Art Spotlight: The Abandoned Hut by Mordecai Buluma

In this blog post Angie and Tashae discuss the symbolism behind The Abandoned Hut by Mordecai Buluma as well as the conservation treatment used to prepare it for exhibition.